Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare but serious autoimmune disorder that weakens voluntary muscles, leading to fatigue and muscle weakness. The condition affects communication between nerves and muscles, making everyday activities like chewing, speaking, or even holding up your head challenging.

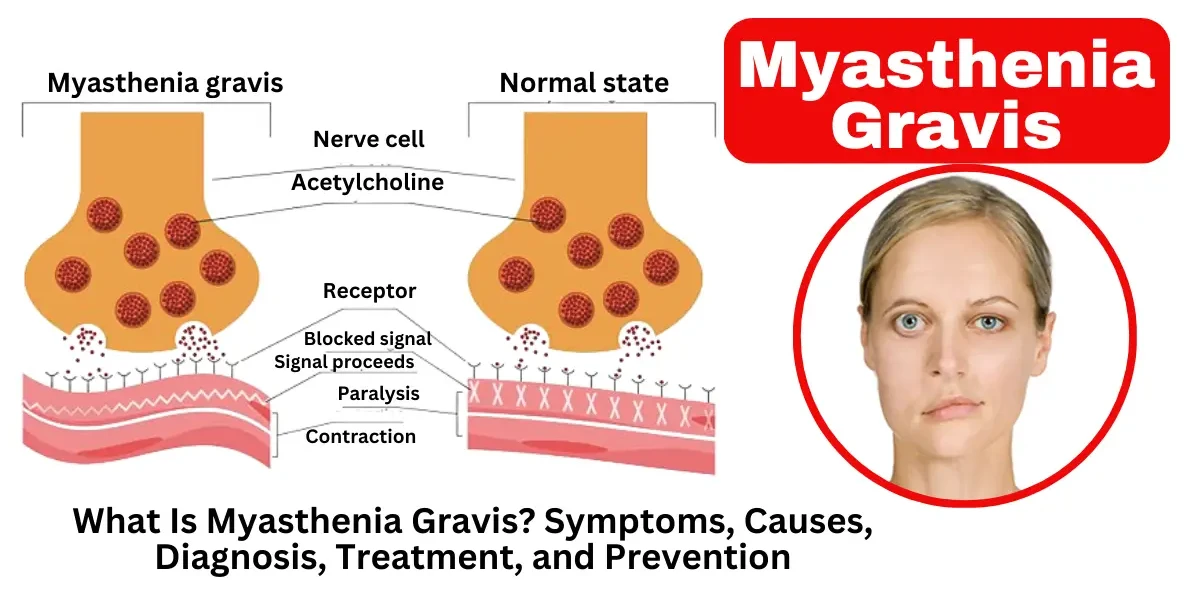

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a long-term autoimmune condition affecting the nerves and muscles, leading to progressive weakness and exhaustion that intensifies with exertion and eases during rest. The condition occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the communication points between nerves and muscles, known as neuromuscular junctions. Specifically, antibodies block, alter, or destroy acetylcholine receptors, which are essential for muscle contraction. This disruption leads to voluntary muscle weakness, particularly in the eyes, face, throat, and limbs. Symptoms may include drooping eyelids (ptosis), double vision (diplopia), difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), slurred speech (dysarthria), and limb weakness. While myasthenia gravis can affect individuals of any age, it is more common in women under 40 and men over 60. Although there is no cure, treatments such as medications, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, and thymectomy can help manage symptoms effectively.

MG is a chronic autoimmune disorder that impairs neuromuscular function, causing persistent fatigue and muscular debility. It is classified into different types based on the antibodies involved, the muscles affected, and the age of onset. The main types include ocular myasthenia gravis, generalized myasthenia gravis, seropositive myasthenia gravis, seronegative myasthenia gravis, and congenital myasthenic syndromes. Each type has distinct clinical features, diagnostic criteria, and treatment approaches.

Ocular myasthenia gravis is a form of MG that primarily affects the muscles controlling eye movement and eyelid function. Patients with this type experience ptosis (drooping eyelids) and diplopia (double vision) but do not typically develop generalized muscle weakness. About 50% of patients with ocular MG progress to generalized MG within two years, especially if left untreated. Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms, the ice pack test (improvement of ptosis with cooling), and antibody testing (though some patients may be seronegative). Treatment includes acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., pyridostigmine) and immunosuppressive therapies such as corticosteroids.

Generalized myasthenia gravis involves weakness in multiple muscle groups beyond the eyes, including the limbs, face, throat, and respiratory muscles. Symptoms may include difficulty chewing, slurred speech (dysarthria), trouble swallowing (dysphagia), and limb weakness. In severe cases, patients may experience myasthenic crisis, a life-threatening condition where respiratory muscles weaken, leading to respiratory failure. Most patients with generalized MG have acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibodies, though some may have muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) antibodies or be seronegative. Treatment involves immunosuppressants (e.g., prednisone, azathioprine), intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), plasma exchange (PLEX), and thymectomy in eligible patients.

Seropositive MG refers to cases where autoantibodies against neuromuscular proteins are detected in the blood. The most common antibody is AChR (acetylcholine receptor), found in 80-90% of generalized MG cases. A smaller subset (about 6-10%) has MuSK (muscle-specific kinase) antibodies, which is associated with more severe bulbar and respiratory weakness and a poorer response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Another rare antibody is LRP4 (low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4), found in 1-2% of MG patients. Seropositive MG often responds well to immunotherapy, and antibody testing helps guide treatment decisions.

Approximately 10-20% of MG patients do not have detectable AChR, MuSK, or LRP4 antibodies and are classified as seronegative. These patients still exhibit classic MG symptoms and respond to standard treatments, but the lack of antibodies makes diagnosis more challenging. Some seronegative patients may have antibodies that are not yet identified, while others may have a different autoimmune mechanism. Diagnosis relies on clinical assessment, electrophysiological tests (repetitive nerve stimulation or single-fiber EMG), and response to cholinesterase inhibitors. Treatment follows similar approaches as seropositive MG, including immunosuppression and symptomatic therapy.

Unlike autoimmune MG, congenital myasthenic syndromes are genetic disorders caused by mutations in genes involved in neuromuscular transmission. Symptoms usually appear in infancy or childhood and include weakness, feeding difficulties, ptosis, and delayed motor development. CMS is classified based on the affected protein (e.g., CHRNE, RAPSN, DOK7 mutations). Treatment depends on the specific subtype; some patients respond to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, while others may worsen with these drugs and require alternative therapies like β2-adrenergic agonists (e.g., salbutamol) or open-channel blockers (e.g., fluoxetine). Genetic testing is essential for accurate diagnosis and management.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is characterized by muscle weakness that worsens with activity and improves with rest. The symptoms vary depending on which muscles are affected, but they typically follow a pattern of fatigue after use. Below, we’ll explore the key symptoms in detail.

One of the most common early signs of MG is weakness in the eye muscles, leading to:

Ptosis (Drooping Eyelids): One or both eyelids may droop, especially after prolonged use of the eyes (like reading or screen time). The degree of drooping can fluctuate throughout the day.

Diplopia (Double Vision): Weakness in the muscles controlling eye movement can cause misalignment, resulting in blurred or double vision. Some people tilt their head to compensate for this.

About 50% of MG patients initially experience only ocular symptoms, but in many cases, the condition progresses to affect other muscles within two years.

When MG affects the face, mouth, and throat, it can cause:

Dysarthria (Slurred or Nasal Speech): Weakness in the facial muscles may make speech sound slow, slurred, or unusually nasal, particularly after prolonged talking.

Difficulty Chewing and Swallowing (Dysphagia): Some people struggle to finish meals because their jaw muscles tire out. In severe cases, choking or aspiration (food entering the airway) can occur.

Facial Weakness: Smiling or making other facial expressions may become difficult, leading to a "mask-like" appearance.

These symptoms can be particularly frustrating because they affect communication and nutrition, significantly impacting daily life.

While MG often starts in the eyes and face, it can also weaken the arms and legs:

Arm Weakness: Simple tasks like brushing hair, lifting objects, or holding arms up (e.g., while blow-drying hair) become exhausting.

Leg Weakness: Walking long distances or climbing stairs may be challenging, and some people feel their legs give out unexpectedly.

Unlike some neurological disorders, MG-related weakness improves with rest, which helps distinguish it from other conditions.

In severe cases, MG can weaken the diaphragm and chest muscles, leading to:

Shortness of Breath: Difficulty taking deep breaths, especially when lying flat.

Respiratory Failure: A life-threatening emergency where breathing becomes insufficient, requiring mechanical ventilation.

This condition, called myasthenic crisis, affects about 15-20% of MG patients at some point and requires immediate medical attention.

A hallmark of MG is that symptoms:

Worsen with activity (e.g., speech becomes harder after long conversations).

Improve with rest (e.g., chewing becomes easier after a break).

Vary throughout the day, often being milder in the morning and worsening by evening.

When to See a Doctor

If you experience unexplained muscle weakness that improves with rest—especially with eye, facial, or swallowing difficulties—consult a neurologist. Early diagnosis and treatment can prevent complications like myasthenic crisis.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder, meaning the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues. While the exact cause remains unclear, researchers have identified several key factors that contribute to the development of this condition. Understanding these causes and risk factors can help in early detection and management.

The main underlying cause of myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune response where the immune system produces antibodies that interfere with nerve-to-muscle communication. In a healthy body, nerve endings release acetylcholine (ACh), a neurotransmitter that binds to receptors on muscle cells, triggering contractions.

In MG, the immune system mistakenly targets:

Acetylcholine receptors (AChR antibodies) – Present in about 85% of MG patients, these antibodies block or destroy ACh receptors, weakening muscle response.

Muscle-specific kinase (MuSK antibodies) – Found in about 6% of MG cases, these affect muscle signaling differently than AChR antibodies.

LRP4 antibodies – A rarer form, seen in a small percentage of patients.

This autoimmune attack leads to muscle fatigue and weakness, particularly after repeated use.

The thymus gland, located behind the breastbone, plays a crucial role in immune function, especially in early life. In many MG patients, this gland is abnormal:

Thymic Hyperplasia (Enlargement) – About 65% of MG patients have an overactive thymus.

Thymoma (Tumor) – Roughly 10-15% develop a thymic tumor, which may worsen autoimmune activity.

Removing the thymus (thymectomy) often improves symptoms, especially in younger patients, suggesting a strong link between the thymus and MG development.

While MG is not directly inherited, certain genetic and environmental factors increase susceptibility:

Genetic Predisposition

Some individuals have HLA (human leukocyte antigen) gene variations that make them more prone to autoimmune diseases.

A family history of other autoimmune disorders (like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis) may slightly increase MG risk.

Triggers and Environmental Factors

Infections (viral or bacterial) may activate the immune system abnormally.

Certain medications, such as beta-blockers, quinine, or some antibiotics, can worsen MG symptoms.

Stress, surgery, or hormonal changes (like pregnancy) may trigger or exacerbate the condition.

MG can affect anyone, but certain groups have a higher likelihood:

Age & Gender Differences:

Women under 40 are more frequently diagnosed, possibly due to hormonal influences.

Men over 60 also have an increased risk, often with more severe symptoms.

Other Autoimmune Conditions: People with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, or type 1 diabetes are at slightly higher risk.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a chronic autoimmune neuromuscular disorder characterized by muscle weakness and fatigue. The progression and severity of the disease can vary among patients, and it is often classified into different stages based on symptom severity, affected muscle groups, and response to treatment. Below are the key stages of myasthenia gravis:

In the early stage of myasthenia gravis, symptoms are typically mild and may come and go. Patients often experience weakness in specific muscle groups, particularly those controlling eye movements (ocular myasthenia), leading to ptosis (drooping eyelids) or diplopia (double vision). Fatigue is common, with symptoms worsening later in the day or after prolonged activity. At this stage, symptoms may be intermittent, making diagnosis challenging. Many patients respond well to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., pyridostigmine), which help improve neuromuscular transmission.

As the disease progresses, muscle weakness extends beyond the eyes to other voluntary muscles, leading to generalized myasthenia gravis. Patients may experience difficulty chewing, swallowing (dysphagia), slurred speech (dysarthria), and weakness in the limbs, neck, or respiratory muscles. Daily activities like climbing stairs, lifting objects, or holding the head upright become challenging. Symptoms fluctuate but tend to worsen with exertion. Immunosuppressive therapies (e.g., corticosteroids, azathioprine) or thymectomy (surgical removal of the thymus gland) may be recommended to manage symptoms and slow disease progression.

In severe cases, patients may experience a myasthenic crisis, a life-threatening condition where respiratory muscles weaken significantly, leading to acute respiratory failure. This requires immediate medical intervention, often involving mechanical ventilation and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasmapheresis to rapidly reduce autoantibodies. Triggers for a crisis include infections, surgery, stress, or medication changes. Patients in this stage require close monitoring in an intensive care unit (ICU) to prevent fatal complications.

A small percentage of patients develop refractory myasthenia gravis, where standard treatments (immunosuppressants, thymectomy, or cholinesterase inhibitors) fail to control symptoms effectively. These individuals may experience persistent, debilitating weakness despite aggressive therapy. Newer treatments like rituximab (a B-cell-depleting agent) or complement inhibitors (e.g., eculizumab) may be considered. Research into targeted biologic therapies continues to improve outcomes for refractory MG patients.

Diagnosing myasthenia gravis (MG) involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and electrophysiological studies. Since the symptoms of MG—such as muscle weakness, ptosis (drooping eyelids), diplopia (double vision), and fatigue—can mimic other neurological disorders, a thorough diagnostic approach is essential for accurate identification and treatment.

Clinical Evaluation and Physical Examination: The diagnostic process begins with a detailed medical history and neurological examination. Doctors assess muscle weakness, checking for signs such as difficulty speaking, chewing, swallowing, or limb weakness that worsens with activity and improves with rest. A key feature of MG is fatigable weakness, meaning symptoms worsen after repetitive use of the affected muscles. The ice pack test may be used for ptosis—applying ice to the eyelids can temporarily improve weakness in some MG patients due to cold-induced enhancement of neuromuscular transmission.

Blood Tests for Autoantibodies: Since MG is an autoimmune disorder, blood tests detect specific autoantibodies that disrupt neuromuscular signaling. The most common antibody is against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR), found in about 85% of generalized MG patients. Another antibody, anti-muscle-specific kinase (anti-MuSK), is present in some AChR-negative patients, particularly those with bulbar or respiratory symptoms. Less commonly, anti-LRP4 antibodies may be detected. Seronegative MG (no detectable antibodies) occurs in a small percentage of patients, requiring further testing.

Electrophysiological Studies: Electrodiagnostic tests help confirm impaired neuromuscular transmission. Repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) shows a decremental response in muscle action potentials after repeated nerve stimulation, indicating fatigue. Single-fiber electromyography (SFEMG) is the most sensitive test for MG, detecting abnormal variability in the timing of muscle fiber activation (jitter). SFEMG is particularly useful in mild or seronegative cases.

Edrophonium (Tensilon) Test: The edrophonium test involves injecting a short-acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (edrophonium chloride) to temporarily improve muscle strength in MG patients. A positive test—where ptosis or eye movement improves within minutes—supports an MG diagnosis. However, due to potential side effects (e.g., bradycardia, hypotension) and the availability of safer tests, this procedure is less commonly used today.

Imaging and Additional Tests: Since thymic abnormalities (thymoma or thymic hyperplasia) are associated with MG, a chest CT or MRI is performed to evaluate the thymus gland. Pulmonary function tests may assess respiratory muscle weakness in severe cases. In atypical presentations, doctors may rule out other conditions like Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), botulism, or mitochondrial myopathies.

The prognosis of myasthenia gravis (MG) varies widely among patients, but with modern treatments, most people can manage their symptoms effectively and maintain a good quality of life. Several factors influence long-term outcomes, including the severity of the disease, early diagnosis, treatment response, and whether complications arise. Below, we explore key aspects that determine the prognosis of MG.

1. Early Diagnosis and Treatment Improve Outcomes

One of the most critical factors in managing myasthenia gravis is early diagnosis. Patients who receive treatment soon after symptoms appear tend to have better long-term outcomes. Delayed diagnosis can lead to worsening muscle weakness and an increased risk of myasthenic crisis—a life-threatening complication where breathing muscles fail. Early intervention with medications like cholinesterase inhibitors or immunosuppressants can help stabilize symptoms and prevent severe disability.

2. Disease Severity and Progression

MG can range from mild (affecting only the eyes) to severe (causing widespread muscle weakness). About 15% of patients have ocular myasthenia gravis, where symptoms remain confined to the eyelids and eye movements. These individuals often have a better prognosis than those with generalized MG, which affects multiple muscle groups. However, in some cases, ocular MG can progress to generalized MG within two years. Patients with severe generalized weakness, especially those who experience respiratory muscle involvement, require more aggressive treatment and closer monitoring.

3. Thymus Abnormalities and Thymectomy

Around 10-15% of MG patients have a thymoma (a tumor of the thymus gland), while many others have thymic hyperplasia (an enlarged thymus). Surgical removal of the thymus (thymectomy) has been shown to improve symptoms in many cases, particularly in patients with early-onset MG (under age 50). Studies suggest that up to 50% of patients who undergo thymectomy experience significant improvement or even remission, though benefits may take months or years to appear.

4. Response to Medications and Therapies

Most patients respond well to standard treatments, such as pyridostigmine (Mestinon), corticosteroids, or immunosuppressants like azathioprine or mycophenolate. However, some individuals have refractory MG, meaning they do not respond adequately to conventional therapies. For these patients, newer treatments like rituximab (a B-cell-depleting drug) or complement inhibitors (eculizumab) may be necessary. Those who achieve good symptom control with medication generally have a favorable prognosis.

5. Risk of Myasthenic Crisis

A myasthenic crisis—a sudden worsening of muscle weakness leading to respiratory failure—is a medical emergency requiring intensive care. About 15-20% of MG patients experience at least one crisis in their lifetime. Factors that increase the risk include infections, surgery, stress, or certain medications (e.g., beta-blockers, certain antibiotics). Patients who survive a crisis with prompt treatment often recover well, but recurrent crises may indicate a more severe disease course.

6. Remission and Long-Term Stability

Some patients achieve spontaneous remission, where symptoms disappear without treatment, though this is rare. More commonly, medication-induced remission occurs, allowing patients to reduce or stop drugs under medical supervision. Studies show that about 30-50% of MG patients eventually reach a stable, minimally symptomatic state with treatment. However, relapses can happen, especially during illness or stress, so ongoing monitoring is essential.

7. Life Expectancy and Quality of Life

With current treatments, most MG patients have a near-normal life expectancy. Advances in immunotherapy and critical care have drastically reduced mortality rates, which were high before the 1950s. While some patients experience persistent fatigue or muscle weakness, many lead active, fulfilling lives with proper management. Supportive therapies, such as physical therapy and speech therapy, can further enhance daily functioning.

Treating myasthenia gravis (MG) focuses on improving muscle strength, suppressing the abnormal immune response, and preventing complications. Since MG affects individuals differently, treatment plans are personalized based on symptom severity, antibody type, and overall health. Below, we explore the key medications, therapies, and surgical options used to manage MG.

The first-line treatment for MG is acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, which help improve nerve-to-muscle communication. The most commonly prescribed drug is pyridostigmine (Mestinon), which slows the breakdown of acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter needed for muscle contractions.

How it works: By increasing acetylcholine availability at the neuromuscular junction, pyridostigmine helps reduce muscle weakness and fatigue.

Dosage: Typically taken every 3–6 hours, with adjustments based on symptom severity.

Side effects: May include stomach cramps, diarrhea, excessive saliva, and muscle twitching.

While effective for mild to moderate symptoms, cholinesterase inhibitors do not stop the autoimmune attack—they only manage symptoms. Patients with severe MG usually require additional therapies.

Since MG is an autoimmune disorder, immunosuppressants are often used to reduce antibody production and inflammation. These medications help prevent further damage to acetylcholine receptors. Common options include:

A. Corticosteroids (Prednisone)

How it works: Rapidly suppresses immune activity, providing relief within weeks.

Usage: Often started at a high dose and tapered down to the lowest effective dose.

Side effects: Long-term use can lead to weight gain, osteoporosis, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

B. Non-Steroidal Immunosuppressants (Azathioprine, Mycophenolate Mofetil, Tacrolimus)

Azathioprine (Imuran): Takes 3–6 months to work but is effective for long-term maintenance.

Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept): Often used as a steroid-sparing agent to reduce side effects.

Tacrolimus (Prograf): Used in refractory cases, particularly for MuSK antibody-positive MG.

These drugs require regular blood monitoring due to potential liver toxicity and increased infection risk.

For patients who don’t respond to standard treatments, biologic therapies offer advanced options:

A. Monoclonal Antibodies (Rituximab, Eculizumab)

Rituximab (Rituxan): Targets B-cells (which produce harmful antibodies), often used in severe or MuSK-positive MG.

Eculizumab (Soliris): Blocks the complement system (part of the immune attack), approved for refractory generalized MG.

These treatments are expensive and usually reserved for severe cases due to potential side effects like infections.

B. Complement Inhibitors (Zilucoplan, Ravulizumab)

Newer drugs like zilucoplan and ravulizumab specifically block the complement pathway, reducing muscle damage. These are showing promise in clinical trials.

In emergencies (such as myasthenic crisis—severe breathing difficulty), fast-acting treatments are needed:

A. Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

How it works: Provides healthy antibodies to temporarily block harmful ones.

Effectiveness: Improves symptoms within days to weeks.

Usage: Given as an infusion over 3–5 days.

B. Plasmapheresis (Plasma Exchange)

How it works: Removes harmful antibodies from the blood.

Effectiveness: Rapid improvement, but effects last only weeks.

Usage: Used before surgery or during severe flare-ups.

Both IVIG and plasmapheresis are short-term solutions, often used while waiting for long-term immunosuppressants to take effect.

Since the thymus gland plays a role in MG (especially in AChR-positive patients), thymectomy (surgical removal) is often recommended:

Who benefits most? Patients with thymoma (tumor) or generalized MG under age 60.

Effectiveness: About 50% of patients experience significant improvement or remission.

Approaches: Minimally invasive (robotic or video-assisted) or open surgery.

Thymectomy is not a cure, but it can reduce medication dependence over time.

Beyond medications, patients should:

Avoid triggers (infections, stress, certain antibiotics like fluoroquinolones).

Exercise carefully (gentle activities like walking or yoga help maintain strength).

Monitor breathing (use of BiPAP in severe cases).

Follow up regularly with a neurologist for treatment adjustments.

Since myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder with no known exact cause, it cannot be entirely prevented. However, certain strategies can help reduce the risk of symptom flare-ups and disease progression in those already diagnosed.

Avoid Known Triggers:

Infections: Viral or bacterial infections can worsen MG symptoms. Practicing good hygiene, staying up-to-date on vaccinations (like flu and pneumonia shots), and avoiding sick contacts can help.

Medications: Some drugs, such as beta-blockers, certain antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones), and muscle relaxants, can exacerbate weakness. Always consult a doctor before taking new medications.

Stress & Fatigue: Physical and emotional stress can trigger or worsen symptoms. Managing stress through relaxation techniques, adequate sleep, and pacing activities is crucial.

Lifestyle Modifications:

Balanced Diet: A nutrient-rich diet supports immune function. Some studies suggest vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids may help regulate autoimmune responses.

Moderate Exercise: Light physical activity (like walking or yoga) can maintain muscle strength without overexertion.

Avoid Extreme Temperatures: Heat can worsen fatigue, while cold may increase muscle stiffness.

Regular Medical Monitoring:

Routine check-ups with a neurologist help track disease progression and adjust treatments early.

Thymus gland evaluation (if applicable) is important, as thymoma removal can improve outcomes.

While these steps don’t guarantee prevention, they can significantly improve quality of life for those with MG or at risk.

If left untreated or poorly managed, myasthenia gravis can lead to serious, sometimes life-threatening complications. Recognizing and addressing these early is critical.

Myasthenic Crisis

A medical emergency where severe muscle weakness leads to respiratory failure.

Symptoms: Extreme difficulty breathing, choking, inability to speak or swallow.

Causes: Infections, medication changes, surgery, or stress.

Treatment: Immediate hospitalization, ventilator support, IV immunoglobulin (IVIG), or plasmapheresis.

Aspiration Pneumonia

Weak throat muscles can cause food or liquids to enter the lungs, leading to infection.

Prevention: Eating slowly, using thickened liquids, and sitting upright while eating.

Long-Term Medication Side Effects

Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone): Can cause osteoporosis, diabetes, weight gain, and high blood pressure.

Immunosuppressants (e.g., azathioprine): Increase infection risk and may affect liver/kidney function.

Mitigation: Regular blood tests, bone density scans, and supplemental calcium/vitamin D.

Muscle Atrophy & Disability

Chronic weakness without proper physical therapy can lead to permanent muscle loss.

Solution: Gentle, supervised exercises to maintain mobility.

Psychological Impact

Anxiety and depression are common due to the unpredictable nature of MG.

Support: Counseling, support groups, and stress management techniques help.

Emergency Plan: Patients should have a crisis plan, including when to seek immediate help.

Vaccinations: Staying updated on vaccines (especially for respiratory infections) lowers complication risks.

Multidisciplinary Care: Collaboration between neurologists, pulmonologists, and physical therapists optimizes outcomes.

By understanding these complications, patients and caregivers can take steps to minimize risks and improve long-term health.

Myasthenia gravis is a complex but manageable condition. Timely detection, appropriate care, and mindful lifestyle changes can greatly enhance daily living. If you or a loved one experiences unexplained muscle weakness, consult a neurologist for evaluation.

While there’s no cure yet, ongoing research brings hope for better therapies. By staying informed and proactive, those with MG can live fulfilling, active lives.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder where the immune system mistakenly attacks the communication between nerves and muscles, leading to muscle weakness. The primary cause is the production of autoantibodies that target acetylcholine receptors (AChR) at the neuromuscular junction, preventing muscle contraction. In some cases, antibodies against muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) or lipoprotein-related protein 4 (LRP4) are involved. Thymus gland abnormalities, such as thymoma (a tumor) or thymic hyperplasia, are also associated with MG, as the thymus plays a role in immune regulation. Genetic predisposition and environmental triggers (e.g., infections, stress) may contribute to disease onset.

While there is no definitive cure for myasthenia gravis, many patients achieve long-term remission or significant symptom control with proper treatment. Some individuals, especially those with ocular MG (affecting only the eyes), may experience spontaneous improvement. Thymectomy (surgical removal of the thymus) can lead to remission in some cases, particularly in young patients with AChR antibodies. However, most patients require ongoing medication management to maintain muscle strength. Early diagnosis and treatment improve the chances of better outcomes.

Yes, most people with myasthenia gravis can lead a near-normal life with appropriate treatment. Advances in immunotherapy, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and supportive care have significantly improved life expectancy and quality of life. However, MG symptoms can fluctuate, and patients may experience exacerbations (myasthenic crises) requiring hospitalization. Lifestyle adjustments, such as avoiding physical exhaustion, stress management, and monitoring for respiratory weakness, are essential. With proper medical care, many individuals manage careers, families, and daily activities effectively.

The first-line treatment for MG includes:

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., pyridostigmine): These medications enhance neuromuscular transmission by preventing acetylcholine breakdown.

Immunosuppressants (e.g., prednisone, azathioprine): Used for long-term immune system modulation.

Thymectomy: Recommended for patients with thymoma or generalized MG (especially AChR-positive patients under 60).

Plasmapheresis or IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin): Used for acute exacerbations or pre-surgical stabilization.

Early intervention helps prevent disease progression and complications.

For MG-related muscle weakness, pyridostigmine (Mestinon) is the most commonly prescribed medication. It improves muscle strength by prolonging acetylcholine action at nerve-muscle junctions. For severe weakness, corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) or other immunosuppressants (e.g., mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab) may be added. In MuSK-positive MG, rituximab shows better efficacy than traditional treatments.

The "best" medicine depends on disease severity and antibody type:

AChR-positive MG: Pyridostigmine + immunosuppressants (prednisone, azathioprine).

MuSK-positive MG: Rituximab or high-dose IVIG may be more effective.

Refractory MG: Newer biologics like eculizumab (Soliris) or ravulizumab (Ultomiris) target complement proteins.

Personalized treatment plans are crucial for optimal management.

Vitamin D: Supports immune regulation and muscle function.

Magnesium: Helps nerve-muscle communication (but excessive amounts may worsen weakness).

B vitamins (B1, B6, B12): Essential for nerve health.

Antioxidants (Vitamin C, E): May reduce oxidative stress.

Always consult a doctor before taking supplements, as some (e.g., magnesium) can interfere with MG symptoms.

A neurologist specializing in neuromuscular disorders is the best doctor for MG. Some centers have MG clinics with multidisciplinary teams, including:

Neuromuscular neurologists

Immunologists

Thoracic surgeons (for thymectomy)

Physical therapists

Seeking care at specialized centers (e.g., Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins, or MG Foundation-designated centers) ensures access to advanced treatments.

Recent advancements include:

Complement inhibitors (eculizumab, ravulizumab): Block immune-mediated nerve damage.

FcRn inhibitors (efgartigimod, rozanolixizumab): Reduce harmful antibodies.

CAR-T cell therapy (experimental): Targets autoimmune B cells.

Gene therapy research: Aims to restore neuromuscular function.

Clinical trials continue to explore novel therapies.

Avoid:

Hard-to-chew foods (steak, raw veggies) if jaw weakness is present.

Choking hazards (dry bread, nuts, sticky foods).

Excessive caffeine/alcohol (can worsen fatigue).

High-magnesium foods (bananas, almonds, spinach) in excess, as magnesium can impair neuromuscular transmission.

Soft, easy-to-swallow diets are recommended during weakness flares.

Notable figures with MG include:

Aristotle Onassis (Greek shipping magnate).

Suzanne Rogers (Days of Our Lives actress).

Sir Lawrence Olivier (legendary actor, had thymectomy).

Their stories highlight that MG can be managed successfully with treatment.

End-stage MG refers to severe, treatment-resistant disease leading to:

Chronic respiratory failure (requiring permanent ventilation).

Profound muscle wasting & disability.

Life-threatening myasthenic crises.

However, with modern therapies, very few patients progress to this stage. Early aggressive treatment and monitoring can prevent severe complications.