Optic neuritis is a condition that can strike suddenly, leaving individuals with blurred vision, eye pain, and even temporary blindness. But what exactly is it, and how does it affect those who experience it? In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what optic neuritis is, its symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment options, along with key details about its prognosis, stages, and prevention.

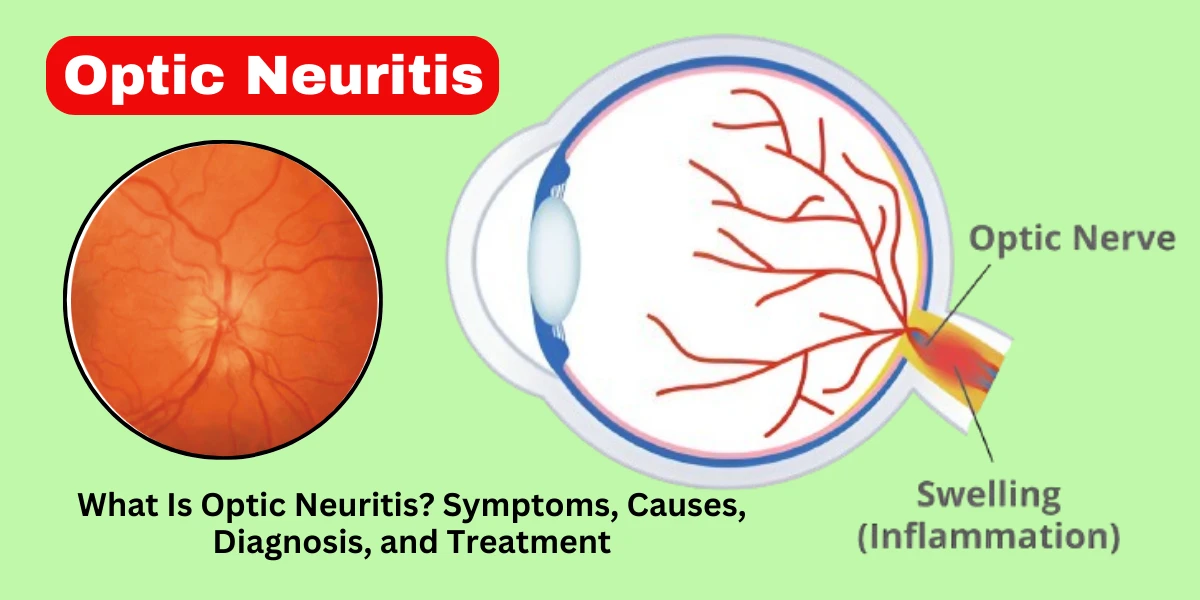

Optic neuritis is an inflammatory condition that affects the optic nerve, the vital cable connecting the eye to the brain. When this nerve becomes inflamed, it disrupts the transmission of visual signals, leading to symptoms like blurred vision, eye pain, and even temporary vision loss. The condition often develops suddenly, with symptoms peaking within a few days before gradually improving.

While the exact cause isn’t always clear, optic neuritis is frequently linked to autoimmune disorders, particularly multiple sclerosis (MS). In fact, for many patients, it serves as the first warning sign of MS. However, not all cases are MS-related—some result from infections, vitamin deficiencies, or even unknown triggers. The good news is that most people recover significant vision over time, though some may experience lingering effects like reduced color perception or mild blurriness.

Optic neuritis can be classified into two main types, depending on its underlying cause and presentation:

This is the most common form, strongly associated with demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS). It usually affects one eye and follows a predictable pattern: sudden vision loss, pain with eye movement, and gradual recovery over weeks to months. Typical optic neuritis often serves as an early indicator of MS, which is why doctors may recommend an MRI scan to check for brain lesions.

Unlike the typical form, atypical optic neuritis may stem from infections, autoimmune disorders (like lupus or neuromyelitis optica), or metabolic deficiencies (such as vitamin B12 deficiency). Key differences include:

Bilateral involvement (affecting both eyes).

More severe or prolonged vision loss.

Different triggers, such as viral infections (e.g., herpes, Lyme disease) or toxins.

Because atypical optic neuritis doesn’t follow the usual MS-linked pattern, it requires a different diagnostic approach and treatment plan, sometimes involving immunosuppressive therapies or antibiotics.

Understanding which type of optic neuritis a patient has is crucial, as it helps doctors determine the best treatment and assess the risk of future complications, such as recurrent attacks or progression to neurological disorders like MS.

Optic neuritis often strikes suddenly, causing a range of visual disturbances and discomfort. The symptoms can vary in severity—some people experience mild blurriness, while others face significant vision loss. Below, we break down the most common optic neuritis symptoms and signs in detail.

1. Blurred or Dimmed Vision

One of the hallmark symptoms of optic neuritis is blurred or dimmed vision, typically in one eye. Patients often describe it as looking through a foggy window or as if a light has been turned down. This happens because inflammation disrupts the optic nerve’s ability to transmit clear signals to the brain. Some people also notice that their vision worsens with physical exertion or heat—a phenomenon known as Uhthoff’s sign, commonly linked to multiple sclerosis (MS).

2. Eye Pain, Especially with Movement

Many individuals with optic neuritis experience sharp or aching pain around the affected eye, which often worsens when moving the eye. This pain usually peaks within the first few days and subsides as the inflammation decreases. Researchers believe this discomfort arises from the swelling of the optic nerve sheath, which becomes sensitive to pressure when the eye moves.

3. Loss of Color Vision (Dyschromatopsia)

A striking symptom of optic neuritis is washed-out or faded color vision. Reds may appear duller, and colors overall seem less vibrant. This occurs because the optic nerve’s fine-tuned fibers responsible for color perception are particularly vulnerable to inflammation. Some patients report that their vision appears “gray” or “sepia-toned” during an attack.

4. Flashes of Light (Photopsia)

Some people with optic neuritis see brief flashes or flickers of light (photopsia), especially when moving their eyes. These flashes are not caused by external light sources but rather by abnormal electrical signals in the inflamed optic nerve. While unsettling, this symptom usually resolves as the inflammation subsides.

5. Reduced Peripheral Vision

In some cases, optic neuritis can lead to blind spots or tunnel vision, where the outer edges of the visual field become dark or blurry. This happens if inflammation affects the nerve fibers responsible for peripheral vision. An automated visual field test can help detect these deficits during diagnosis.

6. Pupillary Abnormalities (Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect - RAPD)

A key clinical sign of optic neuritis is RAPD (Marcus Gunn pupil), where the affected eye responds poorly to light compared to the healthy eye. During an exam, a doctor may shine a light back and forth between the eyes and notice that the affected pupil constricts less—a strong indicator of optic nerve dysfunction.

When to Seek Immediate Medical Attention

While some vision changes may improve on their own, sudden vision loss or severe pain warrants urgent medical evaluation. Early treatment with steroids can speed recovery, and ruling out conditions like MS or infections is crucial for long-term management.

Optic neuritis occurs when the optic nerve becomes inflamed, disrupting vision. While the exact trigger isn’t always clear, research has identified several key causes and risk factors that contribute to this condition. Understanding these can help in early detection, prevention, and effective treatment.

The most common cause of optic neuritis is an autoimmune reaction, where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the protective covering of the optic nerve (myelin sheath). This is often linked to multiple sclerosis (MS)—in fact, about 50% of people with MS will develop optic neuritis at some point, and for 20% of MS patients, it’s the first symptom. Other autoimmune conditions associated with optic neuritis include:

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO or Devic’s disease) – A rare disorder that specifically targets the optic nerves and spinal cord.

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody disease – A recently identified condition causing inflammation in the optic nerve and spinal cord.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and sarcoidosis – These autoimmune diseases can also trigger optic nerve inflammation.

Certain viral and bacterial infections can lead to optic neuritis by causing inflammation or an immune system overreaction. Some of the most notable infections linked to this condition include:

Viral infections (e.g., measles, mumps, herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus, and COVID-19) – These can trigger post-infectious optic neuritis.

Bacterial infections (e.g., Lyme disease, syphilis, tuberculosis, and sinus infections) – These may cause direct nerve damage or secondary inflammation.

Ocular infections (e.g., optic perineuritis) – Rare but possible, especially in immunocompromised individuals.

A lack of essential nutrients or exposure to harmful substances can also contribute to optic nerve damage:

Vitamin B12 deficiency – This vitamin is crucial for nerve health; low levels can lead to optic neuropathy, which mimics optic neuritis.

Toxic/nutritional optic neuropathy – Caused by heavy metals (lead, methanol), excessive alcohol, or certain medications (e.g., ethambutol for tuberculosis).

Radiation exposure – Rarely, radiation therapy near the optic nerve can cause inflammation.

Some people are more prone to optic neuritis due to genetic predisposition or environmental influences:

Age and gender – Most cases occur in adults aged 20-40, and women are 2-3 times more likely to develop MS-related optic neuritis.

Geographical location – Higher rates are seen in northern latitudes, possibly due to lower vitamin D levels, which play a role in immune regulation.

Family history of MS or autoimmune diseases – Genetics can increase susceptibility.

Smoking – Linked to worse outcomes in autoimmune-related optic neuritis.

Optic neuritis doesn’t have a single cause—it’s often the result of immune dysfunction, infections, or nutritional factors. Recognizing these risk factors can help with early diagnosis and treatment, especially for those at higher risk (e.g., young women with a family history of MS). If you experience sudden vision changes, consult a doctor immediately to determine the underlying cause and prevent complications.

Optic neuritis doesn’t develop all at once—it progresses through distinct phases, each with its own symptoms and recovery patterns. Understanding these stages of optic neuritis can help patients and doctors track the condition’s course and determine the best treatment approach.

1. Acute Stage (First 1–2 Weeks)

The acute stage is when symptoms appear suddenly, often reaching their worst within a few days. Patients typically experience:

Rapid vision loss (usually in one eye)

Eye pain, especially with movement

Faded or distorted colors (reds may appear dull or gray)

Increased discomfort with heat or exercise (Uhthoff’s phenomenon)

This stage is caused by active inflammation damaging the myelin sheath (the protective covering of the optic nerve). The immune system mistakenly attacks this layer, disrupting nerve signal transmission. Since this phase is inflammatory, treatments like intravenous (IV) steroids are most effective when given early.

After the initial flare-up, the recovery stage begins. Inflammation gradually subsides, and the optic nerve starts healing. Key characteristics include:

Slow improvement in vision (often starting within 2–4 weeks)

Reduction in pain and light sensitivity

Possible lingering issues, such as slightly blurred vision or trouble distinguishing colors

Some patients recover near-normal vision, while others may have mild but permanent deficits. Research shows that about 90% of patients regain functional vision, though fine details (like reading small print) might remain challenging for some.

3. Chronic Stage (Long-Term Effects)

The chronic stage determines whether optic neuritis leaves lasting damage. Outcomes vary:

Full recovery: Many patients return to baseline vision with no permanent issues.

Partial recovery: Some have mild but persistent reduced contrast sensitivity or color vision changes.

Optic atrophy: In severe or recurring cases, the nerve fibers may degenerate, leading to permanent vision loss (rare).

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are at higher risk for recurrent optic neuritis, which can lead to cumulative nerve damage. Regular monitoring with an ophthalmologist or neurologist is crucial for those with underlying autoimmune conditions.

Diagnosing optic neuritis requires a thorough evaluation because its symptoms can mimic other eye conditions, such as glaucoma or retinal disorders. Doctors use a combination of clinical exams, imaging tests, and lab work to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other possible causes. Here’s a deeper dive into the key diagnostic steps:

1. Medical History and Symptom Review: The first step in diagnosing optic neuritis is a detailed discussion about the patient’s symptoms and medical history. The doctor will ask:

When the vision problems started (sudden vs. gradual)

Whether eye pain worsens with movement (a hallmark of optic neuritis)

If there’s a history of autoimmune diseases (like multiple sclerosis)

Recent infections or vitamin deficiencies (which can trigger inflammation)

This helps determine whether the condition is typical optic neuritis (often linked to MS) or atypical optic neuritis (caused by infections, toxins, or other factors).

2. Visual Acuity Test: A standard eye chart test checks for blurred or reduced vision. People with optic neuritis often struggle to see clearly, especially in one eye. Even if vision seems normal at first glance, subtle deficits may appear when testing each eye separately.

3. Pupillary Light Reflex Test: This exam checks how the pupils respond to light. In optic neuritis, the affected eye may show a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), meaning the pupil doesn’t constrict properly when light is shined into it. This is a strong indicator of optic nerve dysfunction.

4. Ophthalmoscopy (Fundoscopy): An ophthalmologist examines the optic disc (where the optic nerve connects to the eye) for signs of swelling (papilledema). In typical optic neuritis, the optic disc may appear normal at first, but in some cases, mild swelling or pallor (a pale appearance due to nerve damage) can be seen.

5. Visual Field Testing: This test maps peripheral vision. Optic neuritis often causes blind spots (scotomas), particularly in the center of vision. Automated perimetry testing helps detect these subtle deficits.

6. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT is a non-invasive imaging test that measures the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL). Thinning of this layer suggests optic nerve damage and can help track disease progression, especially in MS-related cases.

7. MRI with Contrast: An MRI of the brain and orbits (eye sockets) is the gold standard for confirming optic neuritis. It can reveal:

Optic nerve inflammation (enhancement with gadolinium contrast)

Brain lesions (indicating MS or other neurological conditions)

MRI is especially important for predicting MS risk—if lesions are found, the patient may need long-term monitoring.

8. Blood Tests: If an infection or autoimmune disorder is suspected, blood tests may check for:

Vitamin B12 levels (deficiency can mimic optic neuritis)

Lyme disease, syphilis, or other infections

Autoantibodies (like those seen in neuromyelitis optica/NMO)

9. Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap): In rare or complex cases, a spinal tap may be done to analyze cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for signs of inflammation or MS-related proteins (oligoclonal bands). This is more common if MRI findings are unclear.

An accurate diagnosis ensures the right treatment. For example:

Steroids help typical optic neuritis but may worsen infections like herpes.

MS-linked cases require early disease-modifying therapy to prevent future attacks.

Atypical cases (e.g., from Lyme disease) need antibiotics, not steroids.

Misdiagnosis can delay treatment, so a combination of clinical judgment and advanced imaging is crucial. If you experience sudden vision loss or eye pain, seek prompt evaluation—early intervention improves outcomes.

The prognosis of optic neuritis is generally favorable, with most patients experiencing significant visual recovery. Studies show that about 90% of individuals regain near-normal vision within six to twelve months, though some may have subtle, lingering deficits such as reduced color perception or mild contrast sensitivity issues. The extent of recovery often depends on the underlying cause—patients with typical optic neuritis (associated with multiple sclerosis, or MS) tend to have better outcomes than those with atypical forms (linked to infections or autoimmune disorders like neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, or NMOSD).

For those with MS-related optic neuritis, the condition may serve as an early warning sign of the disease. Research indicates that up to 50% of people with optic neuritis develop MS within 15 years, especially if an MRI shows brain lesions. However, early diagnosis and treatment with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can significantly delay or reduce future relapses. In cases where optic neuritis is not linked to MS, the prognosis is even better, with many patients making a full recovery without further complications.

The duration of optic neuritis varies, but most people follow a predictable timeline:

Acute Phase (First 1-2 Weeks): Symptoms appear suddenly, with peak vision loss and eye pain occurring within days. Movement of the affected eye often worsens discomfort.

Recovery Phase (Weeks to Months): Gradual improvement begins, with many patients noticing vision returning within 2-4 weeks. However, full recovery can take 3-6 months or longer in some cases.

Long-Term Outlook: While most regain functional vision, subtle deficits (like difficulty with night vision or color saturation) may persist. In rare cases (particularly with NMOSD or severe inflammation), permanent vision loss can occur.

Recovery speed can be influenced by treatment. Intravenous steroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) may accelerate healing, shortening the acute phase, though they don’t necessarily change the final outcome. Patients with recurrent optic neuritis (often tied to autoimmune conditions) may experience multiple episodes over years, requiring long-term management to prevent further damage.

When it comes to optic neuritis treatment and medication, the approach depends on the severity of symptoms, underlying causes, and whether conditions like multiple sclerosis (MS) are involved. While some cases resolve on their own, others require medical intervention to reduce inflammation, speed up recovery, and prevent long-term damage. Below, we explore the most common and effective treatment options in detail.

The most widely used treatment for optic neuritis is intravenous (IV) corticosteroids, typically methylprednisolone, followed by an oral steroid taper. This approach helps reduce inflammation in the optic nerve, accelerating vision recovery and decreasing pain. Studies, such as the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial (ONTT), found that IV steroids can speed up recovery, though they may not significantly affect long-term vision outcomes. However, steroids are particularly useful in cases where rapid vision restoration is crucial, such as for professionals who rely heavily on eyesight.

Oral steroids alone (like prednisone) are generally not recommended as a first-line treatment because they may increase the risk of recurrent optic neuritis. Additionally, steroids can have side effects, including mood swings, insomnia, elevated blood sugar, and increased infection risk, so doctors carefully weigh the benefits against potential risks before prescribing them.

For severe cases where vision loss is rapid and steroids fail to improve symptoms, plasma exchange therapy (PLEX) may be considered. This treatment involves removing harmful antibodies from the blood and replacing them with healthy plasma, which can help reduce inflammation when the immune system is overactive. While not a first-line option, PLEX has shown effectiveness in some patients who do not respond to steroids, particularly those with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), a condition often mistaken for MS-related optic neuritis.

If optic neuritis is linked to multiple sclerosis, long-term treatment focuses on disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) to prevent future relapses and slow MS progression. Common DMTs include:

Interferon-beta (Avonex, Rebif) – Reduces flare-ups by modulating the immune system.

Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) – Helps prevent immune attacks on the nervous system.

Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) – A newer monoclonal antibody that targets B-cells involved in MS.

Fingolimod (Gilenya) – Prevents immune cells from attacking the central nervous system.

These medications do not treat acute optic neuritis but are crucial for preventing further nerve damage in MS patients.

Since optic neuritis often causes eye pain, especially with movement, doctors may recommend over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen (Advil) or acetaminophen (Tylenol). In some cases, a short course of low-dose oral steroids may be prescribed solely for pain relief if vision is not severely affected.

While medications are the primary treatment, certain supportive measures can aid recovery:

Resting the eyes – Avoiding screen strain and bright lights during the acute phase.

Vitamin supplementation – Ensuring adequate B12 and vitamin D levels, as deficiencies may worsen nerve health.

Cool compresses – Some patients find relief by applying a cool washcloth to the affected eye.

Research is ongoing into new therapies, including:

High-dose biotin – Shows potential in supporting nerve repair.

Stem cell therapy – Investigated for severe autoimmune-related optic nerve damage.

Neuroprotective agents – Drugs that may shield nerve cells from further injury.

Treatment for optic neuritis is not one-size-fits-all—it depends on the cause, severity, and patient’s overall health. While many recover without intervention, prompt steroid therapy can be crucial in severe cases, and long-term DMTs are essential for those with MS. If you experience sudden vision loss or eye pain, seek immediate medical attention to explore the best treatment options for your situation.

While optic neuritis cannot always be prevented—especially when it is linked to autoimmune conditions like multiple sclerosis (MS)—certain lifestyle and medical strategies may help reduce the risk or severity of attacks.

Manage Underlying Autoimmune Conditions

Since optic neuritis is often associated with MS, early diagnosis and treatment with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can reduce flare-ups. Regular consultations with a neurologist are crucial for those at risk.

Other autoimmune disorders, such as neuromyelitis optica (NMO) or lupus, should also be properly managed to prevent optic nerve inflammation.

Maintain a Nutrient-Rich Diet

Vitamin B12 deficiency has been linked to nerve damage, including optic neuritis. Eating foods like fish, eggs, and fortified cereals—or taking supplements if deficient—may help.

Vitamin D plays a role in immune regulation, and low levels are associated with a higher risk of MS. Sun exposure and supplements (if needed) can support nerve health.

Avoid Smoking and Excessive Alcohol

Smoking increases inflammation and is a known risk factor for MS progression, which can trigger optic neuritis.

Excessive alcohol consumption may worsen nerve damage and should be limited.

Protect Against Infections

Some cases of optic neuritis are triggered by viral or bacterial infections (e.g., Lyme disease, measles, or sinus infections). Staying up-to-date on vaccinations and practicing good hygiene can lower risks.

Monitor Eye and Overall Health

Regular eye exams can detect early signs of optic nerve issues, especially for those with a family history of MS or autoimmune diseases.

Controlling diabetes and high blood pressure is important, as these conditions can contribute to nerve damage over time.

While these steps may not guarantee prevention, they can help reduce risk factors and support overall neurological health.

Most people recover well from optic neuritis, but some may experience long-term complications, particularly if the condition is severe or linked to an underlying disorder like MS.

Permanent Vision Loss

Though rare, severe or recurrent inflammation can lead to optic nerve atrophy (nerve tissue degeneration), causing permanent blurred vision, blind spots, or reduced color perception.

Patients with neuromyelitis optica (NMO) are at higher risk for lasting damage compared to typical MS-related optic neuritis.

Recurrent Episodes

People with MS or NMO often experience multiple attacks of optic neuritis, which can progressively worsen vision over time.

Early treatment with immunosuppressive therapies (e.g., rituximab for NMO) can help prevent recurrences.

Chronic Eye Pain or Discomfort

Some patients report lingering eye pain or discomfort, even after vision improves, possibly due to residual nerve sensitivity.

Optic Nerve Atrophy

Repeated inflammation can lead to thinning of the optic nerve, detectable on an MRI. This may result in mild but permanent vision deficits, such as trouble with contrast or night vision.

Psychological Impact

Vision loss—even temporary—can cause anxiety, depression, or difficulty with daily tasks like driving or reading. Counseling or low-vision rehabilitation may be beneficial.

Those with severe initial vision loss (e.g., near-total blindness in one eye).

Patients diagnosed with NMO or MS, which increase the likelihood of recurrent attacks.

Individuals who delay treatment, as early steroid therapy can improve outcomes.

Optic neuritis is a complex condition that can be both alarming and disruptive, but the good news is that most people recover a significant amount of vision within months. Understanding the symptoms, causes, and treatment options empowers patients to seek timely medical care, which is crucial for the best possible outcome. While some may face long-term complications like mild vision deficits or recurrent episodes, advances in treatments—especially for MS-related cases—have improved prognosis dramatically.

For those at risk of autoimmune diseases, early diagnosis and preventive strategies (such as vitamin D supplementation or disease-modifying therapies) can make a big difference. If you or someone you know experiences sudden vision changes or eye pain, don’t wait—see a doctor immediately. With proper care, many people with optic neuritis go on to live without major visual impairment.

Ultimately, staying informed and proactive is key. Whether you’re recovering from an episode or supporting someone who is, knowing what to expect can ease anxiety and guide effective management. If you have concerns about optic neuritis, discuss them with a healthcare provider to create a personalized plan for your eye and neurological health.

The most common cause of optic neuritis is demyelination (damage to the myelin sheath) due to autoimmune conditions like multiple sclerosis (MS). Other causes include infections, autoimmune diseases (e.g., neuromyelitis optica), and sometimes unknown factors.

Optic neuritis typically improves within 4 to 12 weeks, with many patients regaining near-normal vision. However, recovery time can vary depending on the underlying cause.

Symptoms include:

Vision loss (sudden or gradual)

Reduced color vision (colors appear washed out)

Pain with eye movement (common in optic neuritis)

Visual field defects (e.g., blind spots)

Some medications linked to optic neuritis include:

Ethambutol (tuberculosis treatment)

Amiodarone (heart medication)

Methanol (toxic alcohol)

Certain antibiotics (e.g., linezolid)

While there is no guaranteed cure, most people recover partial or full vision with treatment (e.g., corticosteroids). However, some may have lingering visual deficits, especially if linked to MS or other chronic conditions.

General neuritis symptoms (nerve inflammation) include:

Pain, burning, or tingling

Numbness or weakness

Muscle atrophy (in severe cases)

Impaired function (e.g., vision loss in optic neuritis)

Treatment depends on the cause but may include:

Corticosteroids (e.g., IV methylprednisolone for optic neuritis)

Pain relievers (NSAIDs, gabapentin)

Treating underlying conditions (e.g., MS therapy)

Vitamin supplements (if deficiency is involved)

Diagnostic tests include:

Visual acuity test

Pupillary light reflex test (afferent pupillary defect)

Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

MRI with contrast (to check for MS lesions)

Visual evoked potentials (VEP)

Deficiencies in vitamin B12, vitamin B1 (thiamine), and vitamin B6 can lead to nerve damage and neuritis. B12 deficiency is a common cause of peripheral neuropathy.

Green tea (anti-inflammatory properties)

Turmeric milk (curcumin reduces inflammation)

Water with lemon (hydration + vitamin C)

Aloe vera juice (may help nerve repair)

Animal liver (beef, chicken)

Fish (salmon, tuna)

Eggs and dairy (milk, cheese)

Fortified cereals (for vegetarians/vegans)

Yes, many people recover fully, especially with prompt treatment. However, recovery depends on the cause—some cases (e.g., due to chronic conditions like MS) may have residual symptoms.