Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of genetic disorders characterized by progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. Over time, this condition affects mobility, muscle control, and, in severe cases, heart and respiratory function. While there is currently no cure, advancements in treatment can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

Muscular dystrophy (MD) refers to a group of genetic disorders characterized by progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. These conditions are caused by mutations in genes responsible for muscle structure and function, leading to the gradual breakdown of skeletal muscles over time. Muscular dystrophy can affect people of all ages, but symptoms often appear in childhood, particularly in males, as some forms are X-linked recessive disorders. The severity and progression of the disease vary depending on the type, ranging from mild symptoms with a near-normal lifespan to severe disability and life-threatening complications affecting the heart and respiratory system.

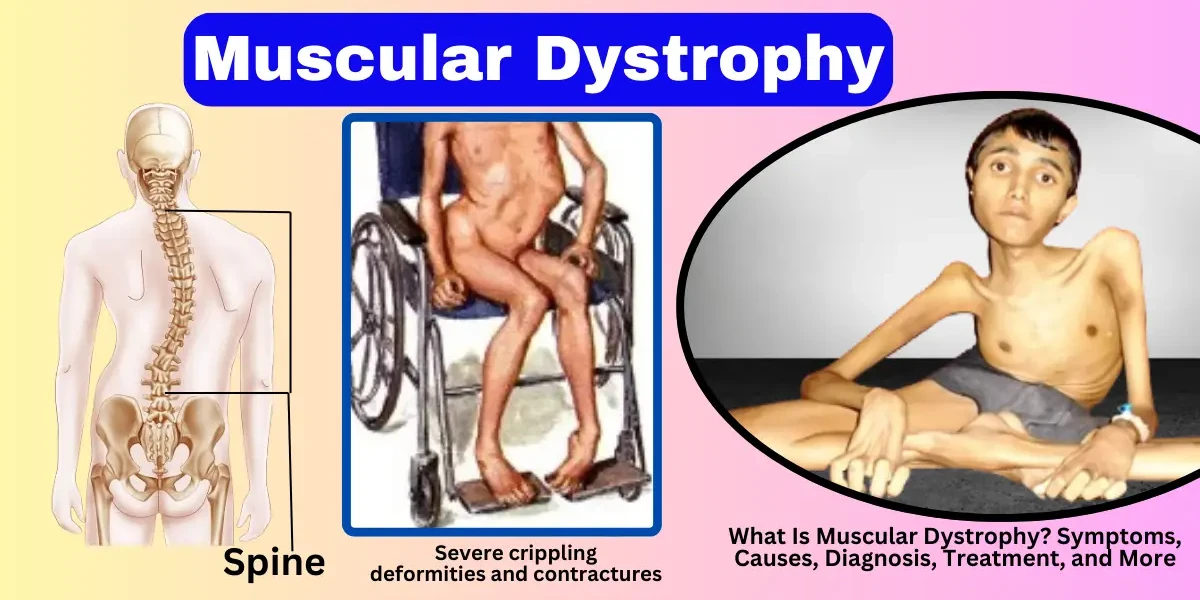

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common and severe form of MD, primarily affecting boys. It is caused by mutations in the DMD gene, which leads to a deficiency of dystrophin, a protein essential for muscle stability. Symptoms usually appear between ages 3 and 5, with children experiencing difficulty walking, frequent falls, and muscle weakness that starts in the legs and pelvis before spreading to other parts of the body. Most individuals with DMD require a wheelchair by their teens, and the condition often leads to life-threatening heart and respiratory complications. While there is no cure, treatments such as corticosteroids, physical therapy, and assisted ventilation can help manage symptoms.

Becker muscular dystrophy is a milder form of MD, also caused by mutations in the DMD gene but resulting in a partially functional dystrophin protein. Symptoms typically appear later than in DMD, often in adolescence or early adulthood, and progress more slowly. Individuals with BMD may experience muscle weakness, cramps, and heart problems, but many remain mobile into their 30s or beyond. Management includes physical therapy, cardiac monitoring, and medications to support muscle and heart function.

Myotonic dystrophy is the most common adult-onset form of MD and is characterized by prolonged muscle contractions (myotonia) and progressive weakness. There are two types: DM1 (caused by a mutation in the DMPK gene) and DM2 (linked to the CNBP gene). Symptoms include muscle stiffness, cataracts, heart arrhythmias, and endocrine issues. Unlike other forms of MD, myotonic dystrophy also affects the central nervous system, leading to cognitive and behavioral changes. Treatment focuses on symptom management, including medications for myotonia and regular monitoring for cardiac and respiratory complications.

FSHD primarily affects the face, shoulders, and upper arms, with weakness progressing to the hips and legs over time. It is caused by a genetic mutation that leads to the abnormal expression of the DUX4 gene. Symptoms usually begin in the teens or early adulthood, with difficulty raising the arms, facial weakness, and shoulder blade deformities. While FSHD progresses slowly and is rarely life-threatening, it can significantly impact mobility and daily activities. Physical therapy and orthopedic interventions are often recommended to maintain function.

Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy encompasses a group of disorders that primarily affect the muscles around the hips and shoulders. LGMD is caused by various genetic mutations, leading to progressive weakness in the pelvic and shoulder girdles. Symptoms can appear in childhood or adulthood, depending on the subtype. Over time, individuals may experience difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and lifting objects. Management includes physical therapy, assistive devices, and, in some cases, cardiac and respiratory support.

Congenital muscular dystrophy is present at birth or appears in early infancy, causing severe muscle weakness, joint deformities, and delayed motor development. Several subtypes exist, each linked to different gene mutations affecting muscle proteins. Some forms of CMD also involve brain abnormalities and intellectual disabilities. Treatment focuses on supportive care, including physical therapy, respiratory assistance, and orthopedic interventions to improve quality of life.

Each type of muscular dystrophy has unique genetic causes, symptoms, and progression patterns. While there is currently no cure, ongoing research into gene therapy and other treatments offers hope for better management and potential future therapies. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary care are crucial in improving outcomes for individuals with MD.

Muscular dystrophy (MD) encompasses a group of genetic disorders that lead to progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. While symptoms vary depending on the specific type of MD, there are common signs that help in early identification. Recognizing these symptoms is crucial for timely diagnosis and intervention. Below, we explore the key symptoms and signs in detail.

Progressive Muscle Weakness: One of the hallmark signs of muscular dystrophy is gradual muscle weakening, which worsens over time. In children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), parents may first notice that their child has difficulty keeping up with peers when running, climbing stairs, or standing up from the floor (often using the Gowers’ maneuver—pushing on their thighs to rise). In adults with myotonic dystrophy, weakness may begin in the hands, neck, or face before spreading to other muscle groups. The pattern of weakness differs among MD types—some affect limbs first, while others weaken facial or shoulder muscles early on.

Frequent Falls and Mobility Challenges: As muscle strength declines, balance and coordination become affected, leading to frequent tripping, stumbling, or falling. Children with DMD might appear clumsy or walk on their toes due to calf muscle tightness. Over time, walking becomes increasingly difficult, and many with severe forms of MD eventually require a wheelchair, typically by their early teens in DMD cases. In limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD), weakness in the hips and shoulders makes activities like lifting objects or getting out of a chair challenging.

Muscle Stiffness, Pain, and Pseudohypertrophy: Some individuals with MD experience muscle stiffness (myotonia), particularly in myotonic dystrophy, where muscles have trouble relaxing after use (e.g., difficulty releasing a grip). Muscle pain and cramping can also occur, especially after physical activity. A unique feature in Duchenne and Becker MD is pseudohypertrophy, where calf muscles appear enlarged due to fat and scar tissue replacing damaged muscle fibers—despite the muscles actually weakening.

Breathing and Swallowing Difficulties: As MD progresses, respiratory muscles weaken, leading to shortness of breath, frequent respiratory infections, and sleep apnea. In advanced stages, some patients require ventilator support to assist breathing. Additionally, weakening of throat and facial muscles can cause dysphagia (trouble swallowing), increasing the risk of choking or aspiration pneumonia.

Cardiac Complications: Several forms of MD, including Duchenne, Becker, and myotonic dystrophy, can affect the heart muscle, leading to cardiomyopathy (enlarged heart) and arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats). Symptoms like fatigue, dizziness, or swelling in the legs may indicate heart involvement, requiring regular cardiac monitoring.

Delayed Motor Development in Children: Infants and young children with congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) may exhibit hypotonia (low muscle tone), leading to delayed sitting, crawling, or walking. Some children never achieve independent walking, while others slowly lose mobility as they grow.

Cognitive and Behavioral Changes (In Some Types): While most MD types primarily affect muscles, Duchenne MD and myotonic dystrophy can also impact cognitive function. Some children with DMD may experience learning disabilities, while adults with myotonic dystrophy might face memory problems, excessive daytime sleepiness, or personality changes.

Progressive Nature of Symptoms: A key characteristic of MD is that symptoms worsen over time. What begins as mild weakness in early childhood can progress to severe disability in later stages. However, the rate of progression varies—DMD advances rapidly, while Becker MD or FSHD may progress more slowly, allowing for decades of functional ability with proper care.

Why Early Recognition Matters

Since symptoms often overlap with other neuromuscular disorders, early medical evaluation is essential. If you or a loved one experiences persistent muscle weakness, frequent falls, or delayed motor milestones, consult a neurologist or neuromuscular specialist for further assessment. Genetic testing, muscle biopsies, and imaging can help confirm a diagnosis and guide treatment strategies.

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is primarily caused by genetic mutations that disrupt the production of proteins essential for muscle function. These defects lead to progressive muscle weakness and degeneration over time. While the exact genetic error varies by MD type, the underlying mechanism involves the failure of muscle fibers to repair themselves, resulting in chronic damage and loss of mobility.

The most well-known form, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene on the X chromosome. Dystrophin acts like a shock absorber for muscle cells—without it, muscles become fragile and easily damaged during movement. Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) also involves the dystrophin gene but allows for some functional protein production, making it less severe than DMD.

Other types of MD stem from different genetic abnormalities:

Myotonic dystrophy results from a repeat expansion in the DMPK or CNBP genes, disrupting muscle relaxation.

Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD) can be caused by defects in multiple genes, including those responsible for muscle membrane stability.

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is linked to chromosome 4, where a shortened DNA region leads to toxic protein production in muscles.

These genetic errors are usually inherited, but in some cases, they occur spontaneously (de novo mutations) with no family history.

The way MD is passed down depends on the type:

X-Linked Recessive (DMD, BMD)

Affects mostly males, as they have only one X chromosome.

Females can be carriers and may pass the gene to their sons.

A mother with the mutation has a 50% chance of passing it to her son.

Autosomal Dominant (Myotonic Dystrophy, FSHD)

Only one parent needs to carry the faulty gene for a child to inherit the condition.

Each child of an affected parent has a 50% chance of developing MD.

Autosomal Recessive (Some LGMD and CMD Types)

Both parents must carry a copy of the mutated gene.

A child has a 25% chance of inheriting the disease if both parents are carriers.

While MD is fundamentally a genetic disorder, certain factors influence its likelihood and severity:

Family History: The strongest risk factor—having a relative with MD increases the chance of being a carrier or developing symptoms.

Gender: Males are at higher risk for DMD and BMD due to X-linked inheritance.

Age of Onset: Some forms (like congenital MD) appear at birth, while others (like myotonic dystrophy) develop in adulthood.

Spontaneous Mutations: In about 1/3 of DMD cases, the mutation occurs randomly with no family history.

Since MD is genetic, it cannot be fully prevented, but genetic counseling and testing can help families assess risks:

Carrier screening identifies if parents carry MD-related mutations.

Prenatal testing (such as amniocentesis) can detect MD in a developing fetus.

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) allows IVF embryos to be screened before implantation.

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of genetic disorders characterized by progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. The progression of the disease varies depending on the type of MD, but it generally follows a pattern of worsening symptoms over time. Below is a detailed breakdown of the typical stages of muscular dystrophy:

In the early stage of muscular dystrophy, symptoms may be mild or even go unnoticed. Children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), the most common type, might show delayed motor milestones, such as walking later than usual or having difficulty running or climbing stairs. In Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), symptoms appear later and progress more slowly. Early signs may include frequent falls, toe walking, or enlarged calf muscles (pseudohypertrophy) due to fat and connective tissue replacing muscle fibers. At this stage, muscle weakness is minimal, and many individuals can still perform daily activities with little assistance.

As the disease progresses, muscle weakness becomes more noticeable, affecting mobility and coordination. In DMD, children between ages 6 and 12 often experience worsening leg weakness, leading to difficulty walking and an increased risk of falls. Many require mobility aids such as braces or wheelchairs by their early teens. In BMD and other milder forms, this stage may extend into adulthood. Upper body strength also declines, making tasks like lifting objects or raising arms challenging. Scoliosis (curvature of the spine) and joint contractures (tightening of muscles and tendons) may develop due to muscle imbalance and reduced movement.

In the advanced stage, muscle weakness becomes severe, leading to loss of independent mobility. Most individuals with DMD lose the ability to walk by their early teens and become wheelchair-dependent. Respiratory muscles weaken, increasing the risk of lung infections and breathing difficulties. Cardiac complications, such as cardiomyopathy (heart muscle weakness), are common in many types of MD. Daily activities like dressing, eating, and bathing often require assistance. Physical therapy, respiratory support, and adaptive equipment become essential to maintain quality of life.

In the late stage, muscular dystrophy affects multiple body systems. Respiratory failure is a leading cause of mortality due to weakened diaphragm and chest muscles. Cardiac complications worsen, requiring medications or pacemakers. Swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) may lead to malnutrition or aspiration pneumonia. Individuals with severe forms of MD, such as DMD, often have a reduced life expectancy, with many surviving into their 20s or 30s with advanced care. In contrast, those with milder forms, like BMD or limb-girdle MD, may live longer but still face significant disability. Palliative and supportive care focus on comfort, respiratory support, and managing complications.

Muscular dystrophy progresses through distinct stages, from mild weakness to severe disability and multi-organ involvement. Early diagnosis and interventions—such as physical therapy, medications, and assistive devices—can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life. Research into gene therapy and new treatments offers hope for slowing disease progression in the future.

1. Clinical Evaluation and Medical History

The diagnostic process for muscular dystrophy (MD) begins with a thorough clinical evaluation and review of the patient’s medical history. Doctors assess symptoms such as progressive muscle weakness, frequent falls, difficulty walking, or delayed motor milestones in children. A family history of muscle disorders is also significant, as many forms of MD are inherited. The physician may examine muscle strength, coordination, reflexes, and gait to identify patterns of weakness that could indicate a specific type of muscular dystrophy.

2. Blood Tests (CK Levels)

Blood tests are commonly used to measure levels of creatine kinase (CK), an enzyme that leaks into the bloodstream when muscle fibers are damaged. Elevated CK levels suggest muscle degeneration, which is a hallmark of muscular dystrophy. While high CK alone does not confirm MD, it helps differentiate muscle diseases from nerve-related conditions. Additional blood tests may check for genetic markers or other muscle-related enzymes to support the diagnosis.

3. Genetic Testing

Genetic testing is the most definitive method for diagnosing muscular dystrophy, as most forms are caused by mutations in specific genes. For example, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is linked to mutations in the DMD gene, while myotonic dystrophy results from a repeated DNA sequence in the DMPK or CNBP genes. Genetic testing can identify these mutations, confirm the type of MD, and help determine inheritance patterns, which is crucial for family planning and genetic counseling.

4. Muscle Biopsy

If genetic testing is inconclusive, a muscle biopsy may be performed. A small sample of muscle tissue is removed and examined under a microscope for signs of degeneration, inflammation, or abnormal protein levels (such as dystrophin in DMD). Immunohistochemistry and Western blotting can detect specific protein deficiencies, aiding in the diagnosis of certain MD subtypes.

5. Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies

Electromyography (EMG) measures electrical activity in muscles, helping distinguish between muscle disorders (like MD) and nerve-related conditions (such as ALS or neuropathy). In MD, EMG typically shows abnormal muscle fiber activity, while nerve conduction studies remain normal. These tests help rule out other neurological disorders that mimic muscular dystrophy symptoms.

6. Imaging Techniques (MRI or Ultrasound)

Muscle imaging, such as MRI or ultrasound, can reveal patterns of muscle damage, fat infiltration, and fibrosis. MRI provides detailed images of muscle degeneration and helps monitor disease progression. In some cases, imaging can identify which muscles are most affected, guiding treatment and physical therapy strategies.

7. Cardiac and Respiratory Assessments

Since some forms of MD affect the heart and lungs, additional tests like echocardiograms, electrocardiograms (ECG), and pulmonary function tests may be conducted. Cardiac involvement is common in myotonic dystrophy and Duchenne MD, while respiratory muscle weakness can lead to breathing difficulties. Early detection of these complications allows for proactive management.

8. Prenatal and Newborn Screening

For families with a history of MD, prenatal testing (such as chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis) can detect genetic mutations in the fetus. Newborn screening for conditions like DMD is also becoming more common, enabling early intervention. Early diagnosis improves outcomes by allowing timely treatment with steroids, physical therapy, or emerging gene therapies.

Muscular dystrophy (MD) refers to a group of genetic disorders characterized by progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. The prognosis varies significantly depending on the type of muscular dystrophy, the age of onset, and the rate of disease progression. While some forms are relatively mild and progress slowly, others are severe and lead to significant disability or early mortality. Below is a detailed discussion of the prognosis associated with different types of muscular dystrophy.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common and severe form of childhood muscular dystrophy, primarily affecting males. Symptoms typically appear between ages 3 and 5, with progressive muscle weakness leading to loss of ambulation by the early teens. As the disease advances, respiratory and cardiac muscles are affected, leading to respiratory failure or cardiomyopathy. With current medical management, including corticosteroids, respiratory support, and cardiac care, many individuals with DMD survive into their late 20s or early 30s. However, without intervention, life expectancy rarely extends beyond the late teens. Advances in gene therapy and exon-skipping drugs offer hope for improved outcomes in the future.

Becker muscular dystrophy is a milder, slower-progressing variant of DMD. Symptoms usually begin in adolescence or early adulthood, with some individuals maintaining the ability to walk into their 40s or 50s. While muscle weakness and cardiac complications (such as dilated cardiomyopathy) are common, the progression is less aggressive than in DMD. Many individuals with BMD have a near-normal lifespan with proper medical care, including regular cardiac monitoring and physical therapy. However, severe cases may lead to significant disability and reduced life expectancy due to heart or respiratory complications.

Myotonic dystrophy is the most common adult-onset form of muscular dystrophy and is characterized by prolonged muscle contractions (myotonia), weakness, and multi-system involvement. DM1 (Steinert’s disease) has a wide variability in severity, with congenital forms being fatal in early childhood, while late-onset cases may only cause mild symptoms. Life expectancy is often reduced due to respiratory failure, cardiac arrhythmias, or complications like dysphagia. DM2 tends to be milder, with slower progression and fewer life-threatening complications. Management focuses on symptom relief, cardiac monitoring, and respiratory support.

Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy encompasses a group of disorders that primarily affect the shoulder and pelvic muscles. The prognosis varies widely depending on the specific genetic subtype. Some forms progress slowly, allowing individuals to remain ambulatory for decades, while others lead to severe disability within 10–20 years of onset. Respiratory and cardiac involvement may occur in certain subtypes, impacting life expectancy. Early intervention with physical therapy, assistive devices, and cardiac/respiratory monitoring can improve quality of life and longevity.

FSHD is one of the more slowly progressive forms of MD, primarily affecting facial, shoulder, and upper arm muscles. Most individuals retain mobility throughout life, though some may require wheelchairs in later stages. Life expectancy is usually normal, but severe cases with respiratory weakness or cardiac involvement may have a poorer prognosis. Management includes physical therapy, orthopedic interventions, and respiratory support if needed.

Congenital muscular dystrophy presents at birth or in infancy with severe muscle weakness, joint contractures, and possible respiratory difficulties. The prognosis depends on the subtype—some children may achieve mild motor function, while others may never walk and require ventilator support. Early death can occur due to respiratory failure, but advances in supportive care have improved survival rates.

The prognosis of muscular dystrophy varies widely based on the type and severity of the condition. While some forms lead to early mortality, others allow for a near-normal lifespan with appropriate medical care. Ongoing research into gene therapy, molecular treatments, and improved supportive care continues to enhance outcomes for individuals with MD. Early diagnosis, multidisciplinary management, and advances in medical technology play crucial roles in improving both life expectancy and quality of life for affected individuals.

While there is currently no cure for muscular dystrophy (MD), several treatments and medications can slow disease progression, manage symptoms, and improve quality of life. The approach varies depending on the type of MD, severity, and individual needs, but here’s a deeper look at the most effective strategies available today.

Corticosteroids, such as prednisone and deflazacort, are the most commonly prescribed drugs for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). These medications help reduce inflammation, delay muscle degeneration, and prolong mobility by slowing the breakdown of muscle fibers. Studies show that boys with DMD who take corticosteroids may walk independently for 2–5 years longer than those who don’t. However, long-term use can lead to side effects like weight gain, bone thinning, and increased infection risk, requiring careful monitoring.

For myotonic dystrophy, medications like mexiletine or carbamazepine may be prescribed to relieve muscle stiffness (myotonia). Additionally, heart medications, including beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors, are often used to manage cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias, which are common in certain types of MD.

In recent years, exon-skipping drugs (e.g., eteplirsen, golodirsen) have been approved for specific genetic mutations in DMD. These therapies work by allowing the body to produce a partially functional dystrophin protein, which can slow muscle deterioration. Another breakthrough is gene therapy (e.g., Elevidys), which delivers a modified dystrophin gene to muscle cells. While still in early stages, these treatments offer hope for slowing disease progression.

Physical therapy plays a critical role in managing MD by preserving muscle strength, flexibility, and joint function. A tailored exercise program—often including low-impact activities like swimming or stretching—helps prevent contractures (tightened muscles and tendons) that can limit movement. Therapists may also recommend orthotic devices (braces or splints) to support weakened limbs and improve posture.

Occupational therapy focuses on maintaining independence in daily activities. Therapists teach adaptive techniques for tasks like dressing, eating, and writing, and may recommend assistive devices such as grab bars, wheelchairs, or voice-activated technology as the disease progresses.

As MD weakens the diaphragm and chest muscles, breathing problems become a major concern, especially in later stages. Non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP) is commonly used to assist with nighttime breathing, while some patients may eventually require a mechanical ventilator. Regular pulmonary function tests help track respiratory health, and cough-assist devices can prevent complications like pneumonia.

Many forms of MD (especially DMD, BMD, and myotonic dystrophy) can lead to heart muscle weakness (cardiomyopathy) or irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias). Regular echocardiograms and EKGs are essential for early detection. Medications like ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, or pacemakers may be used to manage these issues. In severe cases, heart transplantation might be considered.

Research into MD is rapidly advancing, with several promising experimental treatments in development:

Gene-editing (CRISPR): Aims to correct genetic mutations at the DNA level.

Stem cell therapy: Investigates whether muscle stem cells can regenerate damaged tissue.

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs): Help produce functional proteins in certain MD types.

While not yet widely available, clinical trials provide hope for future breakthroughs.

Muscular dystrophy (MD) refers to a group of genetic disorders characterized by progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. Since most forms of MD are inherited, prevention primarily revolves around genetic counseling, early diagnosis, and proactive management rather than traditional preventative measures like vaccines or lifestyle changes.

For individuals with a family history of MD, genetic testing is crucial before planning a pregnancy. A genetic counselor can assess the risk of passing on the defective gene (such as mutations in the dystrophin gene in Duchenne MD) and discuss options like preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) or prenatal testing (amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling) to identify affected embryos. While we cannot yet prevent the genetic mutations causing MD, advancements in gene therapy and CRISPR technology offer hope for future interventions that may correct or mitigate these genetic defects.

For those already diagnosed, preventing rapid disease progression involves a multidisciplinary approach. Physical therapy helps maintain muscle strength and flexibility, while respiratory and cardiac monitoring can prevent secondary complications. Proper nutrition, including a diet rich in anti-inflammatory foods, protein, and essential vitamins, supports muscle health. Additionally, avoiding overexertion and injuries is critical, as muscle damage accelerates degeneration in MD patients. While MD itself cannot yet be prevented entirely, these strategies help delay complications and improve quality of life.

Muscular dystrophy leads to severe and progressive complications as muscle tissue deteriorates over time. The most life-threatening issues involve the respiratory, cardiac, and musculoskeletal systems.

Respiratory Complications:

As the diaphragm and intercostal muscles weaken, breathing becomes increasingly difficult, leading to hypoventilation, recurrent pneumonia, and respiratory failure—the leading cause of death in MD patients. Non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP) and mechanical ventilation may be required in advanced stages. Regular pulmonary function tests and airway clearance techniques help manage these risks.

Cardiac Complications:

Many MD types (e.g., Duchenne, Becker, and myotonic dystrophy) cause cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias due to heart muscle degeneration. Regular echocardiograms and EKGs are essential to monitor heart function. Medications like ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, or pacemakers may be needed to manage heart failure or irregular rhythms.

Musculoskeletal Complications:

Progressive muscle wasting leads to contractures (joint stiffness), scoliosis (spinal curvature), and osteoporosis (bone weakening) due to reduced mobility. Orthopedic interventions, such as braces, spinal rods, or tendon-release surgeries, help maintain posture and mobility. Corticosteroids (like prednisone) can slow muscle degeneration but must be carefully monitored for side effects like weight gain and bone loss.

Swallowing and Nutritional Issues:

Weakness in the throat muscles (dysphagia) increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia and malnutrition. Speech therapists can recommend modified diets, while feeding tubes (PEG tubes) may be necessary in severe cases.

Psychological and Social Complications:

Chronic disability leads to depression, anxiety, and social isolation. Mental health support, counseling, and support groups are vital for emotional well-being.

Each patient’s complications vary based on the type and progression of MD, making personalized care plans essential.

While there is currently no cure for muscular dystrophy, advancements in gene therapy, exon-skipping drugs (like eteplirsen for Duchenne MD), and stem cell research offer hope for future treatments. The focus today remains on early diagnosis, symptom management, and preventing complications to maximize both lifespan and quality of life.

Patients and families should work closely with a neuromuscular specialist, cardiologist, pulmonologist, physical therapist, and nutritionist to create a comprehensive care plan. Clinical trials exploring novel treatments (such as CRISPR-based gene editing and myostatin inhibitors) are ongoing, emphasizing the importance of staying informed about emerging therapies.

Ultimately, supportive care, adaptive technologies (wheelchairs, voice-activated devices), and emotional support play a crucial role in helping MD patients lead fulfilling lives. Although the journey is challenging, medical advancements and holistic care continue to improve outcomes, offering hope for a future where muscular dystrophy can be effectively treated or even cured.

The life expectancy of a person with muscular dystrophy (MD) varies depending on the type and severity of the condition. Some forms, like Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), are more severe, with most individuals living into their late 20s or early 30s due to respiratory or cardiac complications. In contrast, people with Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) may live into their 40s, 50s, or longer with proper medical care. Other milder forms, such as limb-girdle or facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), often have near-normal life expectancy. Advances in treatments, including corticosteroids, respiratory support, and cardiac care, have improved survival rates in recent years.

Muscular dystrophy is primarily caused by genetic mutations that interfere with the production of proteins necessary for healthy muscle function. For example, Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies result from mutations in the DMD gene, which encodes dystrophin, a protein crucial for muscle stability. Other types, like myotonic dystrophy, are linked to repeat expansions in specific genes. These mutations lead to progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. Most forms of MD are inherited in an X-linked recessive (DMD, BMD) or autosomal dominant/recessive pattern (FSHD, limb-girdle).

Three common signs of muscular dystrophy include:

Progressive muscle weakness: Often starting in the legs and pelvis (e.g., difficulty climbing stairs or frequent falls in children).

Delayed motor milestones: Children may walk later than usual or struggle with running and jumping.

Muscle stiffness or hypertrophy: Some individuals develop enlarged calf muscles due to fat and connective tissue replacing muscle fibers (pseudohypertrophy).

Other signs may include fatigue, contractures (joint stiffness), and, in some types, heart or respiratory issues.

Currently, there is no cure for muscular dystrophy, but treatments can manage symptoms and slow progression. Therapies include:

Medications: Corticosteroids like prednisone to delay muscle degeneration.

Physical therapy: To maintain mobility and prevent contractures.

Assistive devices: Braces, wheelchairs, or ventilators for respiratory support.

Experimental treatments: Gene therapy (e.g., Elevidys for DMD) and exon-skipping drugs aim to restore dystrophin production. Research into CRISPR and stem cell therapy offers future hope.

The onset age varies by type:

Duchenne MD: Symptoms appear between ages 2–5.

Becker MD: Typically begins in adolescence or early adulthood.

Congenital MD: Present at birth or shortly after.

Myotonic MD: Can start in infancy (congenital form) or adulthood.

FSHD/Limb-girdle MD: Symptoms may emerge in childhood, teens, or later.

Tests to detect muscle damage include:

Creatine kinase (CK) blood test: Elevated CK levels indicate muscle breakdown.

Electromyography (EMG): Measures electrical activity in muscles, identifying abnormalities.

Muscle biopsy: Examines tissue under a microscope for dystrophic changes.

Genetic testing: Confirms specific mutations causing MD.

Diagnosis involves:

Clinical evaluation: Assessing symptoms, family history, and physical exams.

Blood tests: High CK levels suggest muscle damage.

Genetic testing: Identifies mutations in genes like DMD or DM1.

Muscle biopsy: Reveals fiber necrosis and fat infiltration.

Imaging: MRI or ultrasound to visualize muscle degeneration.

Some tests may cause mild discomfort:

EMG: Small needles insert into muscles may cause brief pain.

Muscle biopsy: Local anesthesia is used, but soreness may follow.

Blood tests: Only a minor pinch during needle insertion.

Yes, MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) effectively detects muscle damage by showing:

Fatty replacement of muscle tissue.

Inflammation or fibrosis.

Asymmetrical muscle involvement in conditions like FSHD.

MRI is non-invasive and provides detailed images without radiation.

MRI is the gold standard for muscle imaging due to its high-resolution soft-tissue contrast. Alternatives include:

Ultrasound: Portable and useful for guiding biopsies.

CT scans: Less detailed for muscles but can show bulk changes.

MRI is superior for muscles, nerves, and connective tissue, while CT scans are better for bones and acute injuries. MRI avoids radiation but is costlier and slower. CT is quicker but exposes patients to X-rays.

Muscle healing involves:

Inflammation: Immune cells remove damaged tissue.

Repair: Satellite cells activate to regenerate fibers.

Remodeling: New muscle matures and strengthens.

Factors aiding recovery include rest, protein-rich nutrition, physical therapy, and treatments like electrical stimulation. In MD, healing is impaired due to genetic defects, making supportive care critical.

You Might Also Like