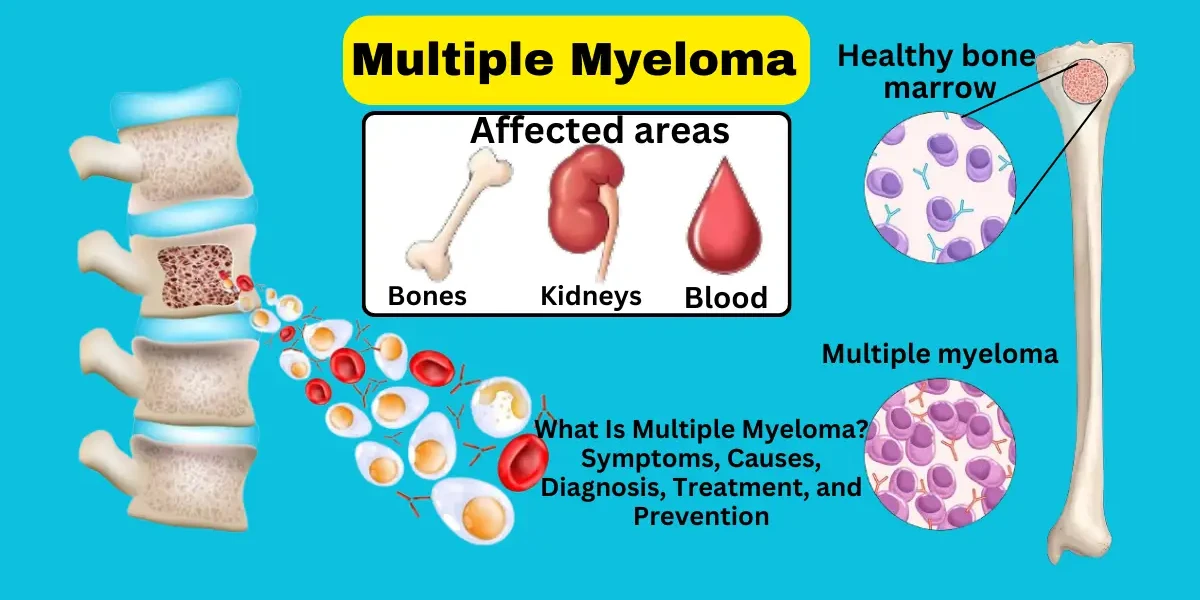

Multiple myeloma is a complex and potentially life-threatening cancer that originates in plasma cells, a type of white blood cell found in the bone marrow. These cells are responsible for producing antibodies that help the body fight infections. When plasma cells become cancerous, they multiply uncontrollably, crowding out healthy blood cells, damaging bones, and impairing kidney function. Although multiple myeloma accounts for only about 1% of all cancers, it is the second most common blood cancer after non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with approximately 35,000 new cases diagnosed annually in the United States alone. The disease primarily affects older adults, with the average age of diagnosis being 69 years, though rare cases can occur in younger individuals.

Despite being incurable in most cases, advancements in treatment—such as targeted therapies, immunomodulatory drugs, and stem cell transplants—have significantly improved survival rates and quality of life for patients. Early detection plays a crucial role in managing the disease, making it essential to recognize symptoms, understand risk factors, and seek timely medical evaluation. This in-depth guide will explore every aspect of multiple myeloma, from its different types and symptoms to diagnosis, treatment options, and prevention strategies.

Multiple myeloma is not a single, uniform disease but rather a group of related conditions that vary in severity and progression. Understanding the different types helps doctors tailor treatment plans to individual patients.

1. Asymptomatic (Smoldering) Myeloma: Smoldering myeloma is an early, precancerous stage where abnormal plasma cells are present in the bone marrow, and elevated levels of monoclonal (M) proteins are detected in blood or urine. However, patients do not experience symptoms such as bone pain, kidney damage, or anemia. About 10-15% of cases progress to active myeloma each year, requiring close monitoring through regular blood tests and imaging.

2. Symptomatic (Active) Myeloma: This is the most common form, where cancerous plasma cells cause significant organ damage, including:

Bone lesions (leading to fractures)

Anemia (due to suppressed red blood cell production)

Kidney dysfunction (from excess protein in urine)

Hypercalcemia (high calcium levels causing confusion and fatigue)

Unlike smoldering myeloma, active myeloma requires immediate treatment to prevent complications.

3. Light Chain Myeloma: In about 15-20% of cases, myeloma cells produce only abnormal light chains (a component of antibodies) rather than complete immunoglobulins. This type can be harder to diagnose because standard blood tests may not detect the light chains, requiring 24-hour urine tests or specialized blood assays.

4. Non-Secretory Myeloma: A rare subtype (1-2% of cases) where plasma cells do not secrete detectable M proteins in blood or urine. Diagnosis relies heavily on bone marrow biopsy and imaging to confirm cancerous growths.

5. Solitary Plasmacytoma: This involves a single tumor of plasma cells, either in bone (osseous plasmacytoma) or soft tissue (extramedullary plasmacytoma). While localized, about 50% of cases eventually progress to multiple myeloma, necessitating long-term follow-up.

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer that affects plasma cells in the bone marrow. The disease can cause a wide range of symptoms, some of which are vague and may resemble other conditions. Below are the key symptoms and signs of multiple myeloma explained in detail:

1. Bone Pain and Fractures: One of the most common symptoms of multiple myeloma is bone pain, particularly in the spine, ribs, pelvis, and skull. This occurs because cancerous plasma cells accumulate in the bone marrow, leading to the weakening of bones. Over time, the bones may develop lytic lesions (holes), increasing the risk of fractures even with minor injuries or stress. Spinal compression fractures can also occur, causing severe back pain and, in some cases, nerve damage.

2. Fatigue and Weakness: Patients with multiple myeloma often experience persistent fatigue and generalized weakness. This happens due to anemia, a condition where the body lacks enough healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen efficiently. The cancerous plasma cells crowd out normal blood-forming cells in the bone marrow, reducing red blood cell production. Fatigue may worsen over time, affecting daily activities and overall quality of life.

3. Frequent Infections: Multiple myeloma weakens the immune system because abnormal plasma cells interfere with the production of normal antibodies that fight infections. As a result, patients may suffer from recurrent infections, such as pneumonia, sinusitis, or urinary tract infections. Bacterial infections are particularly common, but viral and fungal infections can also occur more frequently.

4. Kidney Problems: The overproduction of abnormal proteins (M proteins) by myeloma cells can damage the kidneys, leading to kidney dysfunction or even kidney failure. Symptoms of kidney problems include swelling in the legs (edema), shortness of breath, confusion, and decreased urine output. High calcium levels in the blood (hypercalcemia), another complication of myeloma, can further strain kidney function.

5. Hypercalcemia (High Calcium Levels): When myeloma cells break down bone, excessive calcium is released into the bloodstream, causing hypercalcemia. Symptoms include excessive thirst, frequent urination, constipation, nausea, confusion, and, in severe cases, coma. Hypercalcemia requires prompt medical treatment to prevent complications.

6. Nerve Damage (Peripheral Neuropathy): Some patients experience numbness, tingling, or weakness in their hands and feet due to nerve damage (peripheral neuropathy). This can result from the toxic effects of M proteins or as a side effect of certain myeloma treatments. In rare cases, myeloma may lead to spinal cord compression, causing severe back pain, leg weakness, or loss of bladder/bowel control, which is a medical emergency.

7. Unintentional Weight Loss and Loss of Appetite: Many patients with advanced multiple myeloma experience unexplained weight loss and a reduced appetite. This can be due to the body's increased metabolic demands from cancer, as well as the effects of kidney dysfunction, infections, or high calcium levels.

Multiple myeloma is a complex and relatively uncommon cancer of the plasma cells, which are a type of white blood cell found in the bone marrow. While the exact cause of multiple myeloma remains unclear, researchers have identified several factors that may contribute to its development. Understanding these causes and risk factors is essential for both patients and medical professionals, as it helps in recognizing potential predispositions and implementing early detection strategies where possible.

At its core, multiple myeloma begins with genetic mutations in plasma cells, which are responsible for producing antibodies to fight infections. In healthy individuals, plasma cells grow and divide in a controlled manner, but in multiple myeloma, these cells become cancerous, multiplying uncontrollably and crowding out normal blood cells in the bone marrow. The accumulation of these malignant plasma cells leads to the production of abnormal proteins (M proteins) and can cause bone destruction, kidney damage, and impaired immune function.

While the precise trigger for these mutations is not fully understood, scientists believe that a combination of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors plays a role. Some studies suggest that long-term exposure to certain chemicals, radiation, or chronic immune stimulation (such as from autoimmune diseases or persistent infections) may contribute to plasma cell mutations. Additionally, certain chromosomal abnormalities, such as translocations involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) locus on chromosome 14, are commonly found in myeloma patients, further supporting the genetic basis of the disease.

Although anyone can develop multiple myeloma, certain factors increase the likelihood of its occurrence. These risk factors do not guarantee that a person will develop the disease but are associated with a higher probability.

1. Age: Age is the most significant risk factor for multiple myeloma. The majority of patients are diagnosed in their mid-60s or older, with the average age at diagnosis being around 70. While myeloma can occur in younger individuals, it is rare in those under 40. The increased risk with age may be due to accumulated genetic mutations over time or age-related declines in immune function.

2. Gender: Men are slightly more likely to develop multiple myeloma than women, though the reasons for this disparity are not entirely clear. Hormonal differences, occupational exposures, or variations in immune responses between genders may contribute, but further research is needed.

3. Race and Ethnicity: African Americans have nearly twice the risk of developing multiple myeloma compared to white Americans. The exact cause of this racial disparity is unknown but may involve genetic susceptibility, differences in immune system regulation, or socioeconomic factors affecting healthcare access. Additionally, myeloma is less common in Asian populations, suggesting possible genetic or environmental influences.

4. Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS): MGUS is a benign condition in which abnormal plasma cells produce M proteins but do not cause symptoms or organ damage. However, MGUS is a significant precursor to multiple myeloma, with about 1% of MGUS patients progressing to myeloma each year. The risk factors for MGUS progression include higher levels of M protein, specific genetic abnormalities, and certain immune markers.

5. Family History and Genetic Predisposition: While most cases of multiple myeloma are sporadic, having a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with the disease increases one’s risk. Certain inherited genetic syndromes, such as familial monoclonal gammopathy, may also elevate susceptibility. Researchers continue to investigate specific gene mutations that may predispose individuals to myeloma.

6. Obesity: Obesity has been linked to an increased risk of multiple myeloma, possibly due to chronic inflammation, hormonal changes (such as increased insulin-like growth factors), or altered immune function associated with excess body weight. Maintaining a healthy weight may help mitigate this risk.

7. Exposure to Radiation or Toxic Chemicals: Individuals exposed to high levels of radiation (such as atomic bomb survivors or certain radiation workers) have a higher risk of developing myeloma. Additionally, prolonged exposure to certain industrial chemicals, such as benzene (found in gasoline, rubber manufacturing, and some solvents), pesticides, and asbestos, has been associated with an increased myeloma risk.

8. Immune System Disorders and Chronic Inflammation: Conditions that cause long-term immune system activation, such as autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus) or chronic infections (HIV, hepatitis), may contribute to plasma cell abnormalities. Persistent inflammation can lead to DNA damage in immune cells, increasing the likelihood of cancerous transformation.

9. Other Plasma Cell Disorders: Patients with other plasma cell dyscrasias, such as smoldering multiple myeloma (an early, asymptomatic form of myeloma) or solitary plasmacytoma (a single plasma cell tumor), have an elevated risk of progressing to active myeloma. Close monitoring is necessary for these individuals.

Multiple myeloma is a complex blood cancer that progresses in stages, and understanding these stages is crucial for determining the best treatment approach and predicting long-term outcomes. Staging helps doctors assess how far the disease has spread, whether it has caused organ damage, and how aggressively it needs to be treated. There are two main staging systems used for multiple myeloma: the Durie-Salmon Staging System (an older but still occasionally referenced method) and the Revised International Staging System (R-ISS), which is more precise and widely used today.

Developed in the 1970s, this system classifies myeloma based on tumor burden, bone damage, and lab results (such as hemoglobin, calcium, and M-protein levels). It divides the disease into three stages:

Stage I (Early Disease): The tumor mass is small, with no bone lesions or only a single plasmacytoma. Hemoglobin and calcium levels are near normal, and kidney function is intact.

Stage II (Intermediate Disease): More tumor cells are present, but the patient doesn’t yet meet the criteria for Stage III. Some bone thinning (osteoporosis) or minor fractures may appear.

Stage III (Advanced Disease): High tumor burden with multiple bone lesions, severe anemia (hemoglobin < 8.5 g/dL), high calcium levels (hypercalcemia), or kidney dysfunction (creatinine > 2 mg/dL).

While useful historically, this system is less precise than modern staging because it doesn’t account for genetic risk factors.

The R-ISS, introduced in 2015, is now the gold standard for myeloma staging. It incorporates blood tests, genetic markers, and imaging to provide a more accurate prognosis. The stages are:

R-ISS Stage I (Low Risk): Patients have normal LDH levels and no high-risk chromosomal abnormalities (like del(17p) or t(4;14)). The median survival is 8-10 years or more with treatment.

R-ISS Stage II (Intermediate Risk): Patients don’t fit into Stage I or III. Survival averages 5-7 years, depending on treatment response.

R-ISS Stage III (High Risk): Patients have elevated LDH levels and/or high-risk genetic changes. Survival drops to 2-3 years without effective therapy, but newer treatments (like CAR-T cells) are improving outcomes.

Staging directly impacts treatment decisions:

Stage I (Smoldering Myeloma): May not require immediate treatment but needs close monitoring.

Stage II/III (Active Myeloma): Requires chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or stem cell transplant.

High-Risk Genetic Features: May need more aggressive therapies, such as proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib) or clinical trials.

Diagnosing multiple myeloma requires a careful and systematic approach because its symptoms often mimic other conditions, such as arthritis, osteoporosis, or chronic infections. As your doctor, I want to walk you through the key steps we take to confirm whether myeloma is present, assess its severity, and determine the best treatment plan.

Before any tests, we review your symptoms—such as persistent bone pain, fatigue, frequent infections, or unexplained kidney problems—and ask about family history, since myeloma can sometimes run in families. During the physical exam, we check for signs like pale skin (anemia), bone tenderness, or swelling in areas where tumors may be present.

Blood tests are crucial in detecting myeloma-related abnormalities:

Complete Blood Count (CBC): Checks for anemia (low red blood cells), which is common in myeloma because cancerous plasma cells crowd out healthy blood cell production.

Serum Protein Electrophoresis (SPEP) & Immunofixation: These tests identify monoclonal (M) proteins, abnormal antibodies produced by cancerous plasma cells.

Beta-2 Microglobulin: High levels indicate more advanced disease.

Serum Free Light Chains (FLC) Assay: Measures kappa and lambda light chains—an imbalance suggests myeloma, even if SPEP is normal.

Kidney Function Tests (Creatinine, BUN): Myeloma can damage kidneys, so we monitor these closely.

24-Hour Urine Collection: Checks for Bence Jones proteins (free light chains), which are filtered by the kidneys and can cause damage.

Urine Protein Electrophoresis (UPEP): Confirms if abnormal proteins are being excreted.

This is the gold standard for confirming myeloma. We take a small sample from your hipbone (or sometimes the sternum) under local anesthesia. The sample is examined for:

Plasma Cell Percentage: Normally, plasma cells make up <5% of bone marrow. In myeloma, this jumps to ≥10%, often much higher.

Cytogenetic (Genetic) Testing: Looks for high-risk mutations like del(17p), t(4;14), or 1q amplification, which affect prognosis and treatment choices.

Because myeloma weakens bones, we use imaging to detect damage:

X-rays (Skeletal Survey): The traditional method to spot lytic lesions (holes in bones).

MRI: More sensitive for spinal or soft tissue involvement and early bone changes.

PET-CT Scan: Detects active myeloma tumors and measures disease spread.

Low-Dose CT or Whole-Body MRI (in some cases): Used if X-rays miss small lesions.

We rule out other disorders like:

MGUS (Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance): Has M proteins but no symptoms or organ damage.

Smoldering Myeloma: Higher M protein levels than MGUS but still no symptoms.

Other Cancers (Lymphoma, Metastatic Bone Disease): Require different treatments.

Once myeloma is confirmed, we determine its stage using:

Revised International Staging System (R-ISS): Combines blood tests (albumin, beta-2 microglobulin) and genetic risk factors to classify disease as Stage I (low risk) to Stage III (high risk).

The prognosis of multiple myeloma—meaning the likely course and outcome of the disease—varies significantly from patient to patient, depending on several key factors. While myeloma remains incurable for most, advances in treatment have dramatically improved survival rates over the past two decades. The average 5-year survival rate is now around 55%, but this can range from less than a year for aggressive, high-risk cases to over 10 years for patients with slow-growing disease who respond well to therapy.

Several critical factors influence prognosis:

Stage at Diagnosis – Patients diagnosed at Stage I (early disease with minimal organ damage) typically have better outcomes than those with Stage III (widespread bone lesions, kidney failure, or high tumor burden). The Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) helps predict survival based on blood markers like beta-2 microglobulin and albumin, as well as genetic abnormalities.

Genetic Abnormalities – Certain chromosomal changes, such as deletion 17p, t(4;14), or gain 1q, indicate high-risk myeloma, which progresses faster and is more resistant to treatment. Patients with these mutations may require more aggressive therapies, such as combination drugs or clinical trials.

Response to Treatment – Patients who achieve complete remission (no detectable cancer) or minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity after therapy tend to live longer. Those who relapse quickly or develop refractory myeloma (resistant to multiple drugs) face a tougher prognosis.

Age and Overall Health – Younger, fitter patients (under 65) who can tolerate stem cell transplants often have better outcomes. Older adults or those with heart disease, kidney failure, or diabetes may struggle with treatment side effects, impacting survival.

Kidney Function – Severe kidney damage (creatinine >2 mg/dL) at diagnosis reduces survival unless reversed with prompt treatment.

While myeloma remains a serious illness, new therapies like CAR-T cells, bispecific antibodies, and next-gen proteasome inhibitors are extending life expectancy. Regular monitoring and personalized treatment plans are crucial for managing the disease long-term. If you have myeloma, your hematologist will discuss your specific prognosis based on these factors and work with you to optimize your care.

Multiple myeloma is a complex blood cancer that requires a personalized treatment approach based on disease stage, patient age, overall health, and genetic factors. While there is no definitive cure for most patients, modern therapies can effectively control the disease, extend survival, and improve quality of life. Treatment strategies typically involve a combination of medications—including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted drugs, and stem cell transplants—along with supportive care to manage symptoms and complications.

For newly diagnosed patients, the first step is induction therapy, which aims to rapidly reduce cancer cell levels before considering more aggressive treatments like stem cell transplantation. The most common regimens include:

Proteasome Inhibitors (Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib) – These drugs block the proteasome, a cellular structure that breaks down proteins in myeloma cells. By disrupting this process, cancer cells accumulate toxic proteins and die. Bortezomib (Velcade) is often given subcutaneously or intravenously, usually in combination with other drugs. Carfilzomib (Kyprolis) is more potent and used in relapsed cases. Side effects may include neuropathy (nerve pain), fatigue, and low blood counts.

Immunomodulatory Drugs (Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide, Thalidomide) – These medications stimulate the immune system to attack myeloma cells while also cutting off their blood supply. Lenalidomide (Revlimid) is a cornerstone of myeloma treatment, often paired with dexamethasone (a steroid) to enhance effectiveness. Thalidomide (an older drug) is less commonly used today due to its higher risk of blood clots and nerve damage, but it may still be an option in certain cases.

Monoclonal Antibodies (Daratumumab, Elotuzumab, Isatuximab) – These target-specific proteins on myeloma cells, marking them for destruction by the immune system. Daratumumab (Darzalex) is particularly effective, often combined with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (DRd regimen) or bortezomib and dexamethasone (DVd regimen). Infusion reactions (fever, chills) can occur but are manageable with pre-medications.

Steroids (Dexamethasone, Prednisone) – High-dose steroids reduce inflammation and enhance the effects of other myeloma drugs. Dexamethasone is commonly used in combination therapies but can cause insomnia, high blood sugar, and mood swings.

For younger, fit patients (usually under 70), high-dose chemotherapy followed by an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is a standard approach. This involves:

Stem Cell Collection – Patients receive growth factor injections to mobilize stem cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream, where they are harvested and frozen.

High-Dose Chemotherapy (Melphalan) – A strong chemo drug wipes out remaining myeloma cells (and most healthy bone marrow).

Stem Cell Reinfusion – The stored stem cells are returned to the patient to rebuild healthy bone marrow.

While ASCT can lead to long remissions (5+ years for some), it is not a cure, and most patients eventually relapse. Allogeneic transplants (using donor cells) are rarely used due to high risks of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and infection.

After induction or transplant, maintenance therapy helps keep the disease in check. The most common option is low-dose lenalidomide (Revlimid), which has been shown to prolong remission and improve survival. Some patients may receive bortezomib or daratumumab maintenance, especially if they have high-risk genetic features.

When myeloma returns (relapses) or stops responding to initial therapy (refractory), newer and more aggressive treatments are used, including:

Next-Generation Proteasome Inhibitors (Carfilzomib, Ixazomib) – More potent than bortezomib, with less neuropathy risk.

New Immunomodulatory Drugs (Pomalidomide) – Works even if lenalidomide fails.

Anti-CD38 Antibodies (Daratumumab, Isatuximab) – Often combined with other drugs for better responses.

XPO1 Inhibitor (Selinexor) – A novel drug that forces cancer cells to retain tumor-suppressing proteins, leading to their death.

Bispecific Antibodies (Teclistamab, Talquetamab) – These drugs bridge T-cells to myeloma cells, triggering immune destruction.

CAR-T Cell Therapy (Ide-cel, Cilta-cel) – A groundbreaking treatment where a patient’s own T-cells are genetically reprogrammed to hunt and kill myeloma cells. CAR-T therapy has shown remarkable success in advanced cases, with some patients achieving complete remission for years.

Myeloma treatment can cause significant side effects, so supportive care is crucial:

Bone Strengthening (Bisphosphonates – Zoledronic Acid, Pamidronate) – Prevents fractures by reducing bone breakdown.

Blood Clot Prevention (Aspirin, Anticoagulants) – Needed for patients on immunomodulatory drugs.

Infection Prevention (Antibiotics, Vaccinations) – Due to weakened immunity, pneumonia and shingles vaccines are critical.

Pain Management (Radiation, Opioids) – For severe bone pain, localized radiation can provide relief.

Research is rapidly advancing, with promising experimental therapies in clinical trials:

Dual-Antibody Therapies – Targeting multiple myeloma proteins simultaneously.

Nanobody Drugs – Smaller, more precise antibodies with fewer side effects.

Vaccine-Based Immunotherapy – Training the immune system to recognize myeloma cells.

As your doctor, I want to be very clear: we do not yet know how to definitively prevent multiple myeloma because its exact causes remain uncertain. However, based on extensive research into risk factors, there are several strategies that may help reduce your risk or detect the disease early when it's most treatable.

Unlike some cancers tied to clear lifestyle factors (like lung cancer from smoking), multiple myeloma develops from complex interactions between genetics, immune dysfunction, and environmental exposures. That said, we can focus on risk reduction rather than absolute prevention.

Monitor Precancerous Conditions

If you have MGUS (Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance)—a benign condition where abnormal proteins appear in your blood—you need annual blood and urine tests. About 1% of MGUS cases progress to myeloma each year, so early tracking is crucial.

Similarly, smoldering myeloma (a more advanced precancerous stage) requires close hematologist supervision, as some patients now receive early treatment to delay progression.

Minimize Environmental Risks

Radiation exposure (e.g., nuclear workers, radiation therapy survivors) is linked to myeloma. While you can't avoid medical radiation when necessary, discuss shielding options with your doctor.

Chemical exposures like benzene (found in gasoline, plastics, and pesticides) may increase risk. If you work in manufacturing or agriculture, use protective gear and follow safety protocols.

Lifestyle Modifications

Maintain a healthy weight: Obesity causes chronic inflammation, which may fuel plasma cell mutations. Aim for a BMI under 30.

Exercise regularly: Physical activity supports immune function and bone strength, potentially reducing myeloma-related complications.

Don’t smoke: While smoking isn’t a direct cause, it worsens overall cancer risk and treatment outcomes.

Dietary Considerations

Some studies suggest vitamin D deficiency might play a role in blood cancers. Ask your doctor about checking your levels and supplementing if needed.

A Mediterranean diet (rich in fish, olive oil, and vegetables) may lower inflammation, though more research is needed for myeloma specifically.

Genetic Counseling (For High-Risk Families)

If multiple relatives have had myeloma or MGUS, consider genetic testing for mutations like FAM46C or DIS3. While you can’t change genes, knowing your risk allows for earlier screening.

Since myeloma is often incurable in advanced stages, catching it early—when it’s still smoldering or asymptomatic—can dramatically improve outcomes. If you have risk factors, regular complete blood counts (CBC), serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), and free light chain assays can detect abnormalities before symptoms arise.

Now, let’s discuss what happens if myeloma progresses untreated. As your physician, my goal is to help you avoid these complications through proactive care.

Myeloma cells activate osteoclasts, which dissolve bone, causing lytic lesions (holes in bones).

Spine collapses (vertebral fractures) are common, leading to:

Severe back pain

Loss of height

Spinal cord compression (a medical emergency causing paralysis if untreated)

Prevention/Treatment:

Bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid) slow bone loss.

Radiation therapy stabilizes painful lesions.

Kyphoplasty (a procedure to cement fractured vertebrae).

Myeloma proteins (Bence Jones proteins) clog kidney tubules, while high calcium from bone breakdown further damages them.

Symptoms:

Swelling in legs (edema)

Foamy urine (proteinuria)

Fatigue from toxin buildup

Prevention/Treatment:

Hydration (3+ liters/day) to flush proteins.

Dialysis if kidneys fail.

Plasmapheresis to filter harmful proteins in severe cases.

Normal plasma cells make antibodies to fight infections. Myeloma cripples this system, leaving patients vulnerable to:

Pneumonia (from bacteria like Streptococcus)

Shingles (herpes zoster reactivation)

Bloodstream infections (sepsis)

Prevention/Treatment:

Vaccinations (pneumococcal, flu, COVID-19—though avoid live vaccines).

IVIG (immunoglobulin therapy) if antibody levels are critically low.

Prophylactic antibiotics during high-risk treatments.

Bone breakdown floods the blood with calcium, causing:

Confusion (“myeloma brain”)

Excessive thirst and urination

Heart rhythm disturbances

Prevention/Treatment:

Bisphosphonates to stabilize bones.

IV fluids and diuretics to flush calcium.

Calcitonin or steroids in emergencies.

Myeloma crowds out red blood cell production, causing fatigue, and platelet loss, leading to easy bruising.

Prevention/Treatment:

Erythropoietin (EPO) injections to boost RBCs.

Blood transfusions in severe cases.

Myeloma proteins or chemotherapy drugs like bortezomib can damage nerves, causing:

Numbness in hands/feet

Burning pain

Muscle weakness

Prevention/Treatment:

Dose adjustments of neurotoxic drugs.

Gabapentin or duloxetine for pain relief.

Myeloma thickens blood, and treatments like lenalidomide increase clot risk.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) can be fatal.

Prevention:

Blood thinners (aspirin, warfarin, or rivaroxaban) for high-risk patients.

Compression stockings during hospitalization.

Ironically, myeloma treatments (like alkylating chemo or stem cell transplants) slightly increase the risk of leukemia or MDS (myelodysplastic syndrome) years later.

Mitigation:

Regular blood monitoring post-treatment.

Avoiding unnecessary radiation.

Multiple myeloma is a challenging but increasingly manageable cancer. Early detection, personalized treatment, and ongoing research offer hope for longer survival and better quality of life. If you or a loved one experience symptoms, consult a hematologist promptly.

While multiple myeloma is generally considered incurable, many patients can live for years with effective treatment. Recovery in the traditional sense (complete and permanent cure) is rare, but remission—where the disease is under control or undetectable—is achievable. With advancements in chemotherapy, immunotherapy, stem cell transplants, and targeted therapies, survival rates have significantly improved. Some people live 10 years or more after diagnosis, especially when diagnosed early.

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer. More specifically, it is a plasma cell cancer. Plasma cells are a type of white blood cell found in the bone marrow that helps fight infection by producing antibodies. In multiple myeloma, these plasma cells become abnormal and multiply uncontrollably, crowding out healthy blood cells and producing abnormal proteins called M proteins or monoclonal proteins.

Diagnosis usually involves a combination of tests and findings, which may include:

M-protein in blood or urine (detected via serum protein electrophoresis or urine protein electrophoresis)

Bone marrow biopsy showing ≥10% clonal plasma cells

CRAB criteria (signs of organ damage):

C: High calcium levels (hypercalcemia)

R: Renal (kidney) insufficiency

A: Anemia

B: Bone lesions (seen on X-rays or MRIs)

Additionally, newer diagnostic tools may look at free light chains and imaging (MRI, PET-CT) for early signs.

Most patients don’t have obvious symptoms early on, but common first signs that prompt evaluation include:

Persistent bone pain (especially in the back or ribs)

Fatigue or weakness due to anemia

Frequent infections

Kidney issues

Unexplained weight loss

Diagnosis often begins after routine blood work shows elevated protein levels or low blood counts, leading to more detailed testing.

Here are 7 common signs to look out for:

Bone pain (especially in the back, ribs, or hips)

Frequent infections (due to weakened immune system)

Fatigue or weakness (from anemia)

Unexplained weight loss

Excessive thirst or urination (related to high calcium levels)

Kidney problems (e.g., elevated creatinine)

Numbness or weakness (from spinal cord compression or nerve damage)

The exact cause of multiple myeloma is not fully understood, but risk factors include:

Age (most cases occur after age 60)

Gender (more common in men)

Family history of blood cancers

Race (African Americans have a higher risk)

Exposure to certain chemicals or radiation

Pre-existing conditions like MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance), which can evolve into myeloma

It's believed to result from genetic mutations in plasma cells, often influenced by environmental and immune factors.

As of now, multiple myeloma is not considered curable, but it can be managed effectively for long periods. Many patients experience long remission after treatment. Some even maintain minimal residual disease (MRD-negative status), where cancer is undetectable at very sensitive levels. Treatments continue to improve, offering better quality and length of life.

High-risk groups include:

Older adults (especially over age 60)

African American ethnicity (twice the risk of white populations)

Men

People with a family history of myeloma or MGUS

Those with autoimmune disorders

Individuals exposed to radiation or chemicals (like benzene)

Not directly. Vitamin B12 deficiency isn't a classic symptom of myeloma, but it can co-exist or contribute to similar symptoms, such as:

Fatigue

Nerve damage (neuropathy)

Pale skin or anemia

Myeloma patients may develop anemia, which sometimes mimics B12 deficiency, or have digestive issues that impair B12 absorption.

Multiple myeloma primarily affects the bone marrow, but its impact extends to several organs:

Bones: causing pain and fractures

Kidneys: due to excess light chains or calcium

Blood: leading to anemia and reduced immunity

Nervous system: spinal cord compression or peripheral neuropathy in advanced cases

B12 deficiency mainly affects:

The nervous system: causing nerve damage, numbness, tingling, and difficulty walking

The brain: leading to memory issues, confusion, or even dementia-like symptoms

The blood: resulting in megaloblastic anemia (large red blood cells)

If left untreated, the neurological damage can become irreversible.

Several diseases can mimic the symptoms or lab findings of myeloma:

MGUS (Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance)

Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia

Bone metastases from other cancers

Osteoporosis

Amyloidosis

Chronic kidney disease

Anemia of chronic disease

Vitamin D or B12 deficiency