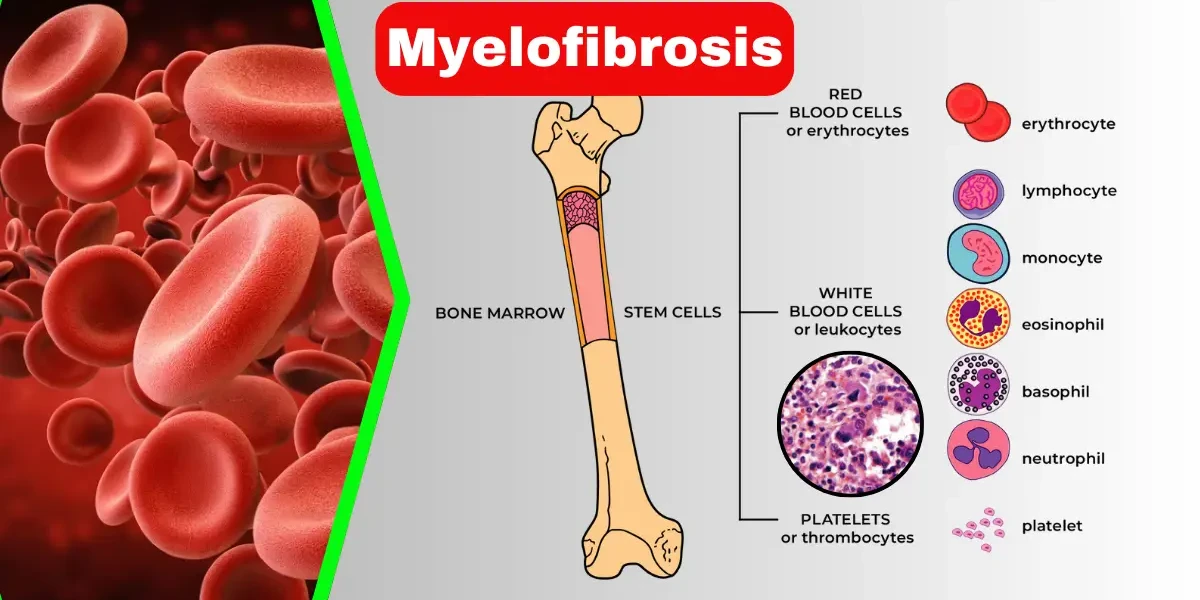

Myelofibrosis is a rare and serious bone marrow disorder that disrupts the body’s ability to produce healthy blood cells. It is classified as a type of myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), where the bone marrow is gradually replaced by scar tissue (fibrosis), leading to severe anemia, fatigue, and an enlarged spleen.

This condition can develop on its own (primary myelofibrosis) or as a progression from other blood disorders like polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia (secondary myelofibrosis). While a complete remedy is not yet available, treatment options can help control symptoms and promote a better life.

Myelofibrosis is a rare and chronic bone marrow disorder that disrupts the body’s normal production of blood cells. It is classified as a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), a group of conditions where the bone marrow—the spongy tissue inside bones responsible for making blood cells—becomes dysfunctional. In myelofibrosis, healthy bone marrow is gradually replaced by fibrous scar tissue, a process called fibrosis. This scarring impairs the marrow’s ability to produce enough red blood cells (leading to anemia), white blood cells (increasing infection risk), and platelets (causing bleeding or clotting problems).

The disease often leads to an enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) because the spleen starts compensating for the failing bone marrow by producing blood cells itself, which can cause pain and discomfort. Myelofibrosis can develop on its own (primary myelofibrosis) or as a complication of other blood disorders (secondary myelofibrosis). While it is most commonly diagnosed in adults over 50, it can occur at any age. Although there is currently no cure, treatments such as medications, blood transfusions, and stem cell transplants can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

Myelofibrosis is categorized into two main types based on how it develops:

Primary myelofibrosis occurs when the disease arises independently, without any prior blood disorder. It is caused by genetic mutations, most commonly in the JAK2, CALR, or MPL genes, which lead to abnormal blood cell production and eventual bone marrow scarring. Patients with PMF may experience a range of symptoms, from mild fatigue in early stages to severe complications like leukemia transformation in advanced cases. Because PMF progresses slowly in some patients but aggressively in others, doctors use risk stratification tools (such as the Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System, DIPSS) to predict disease course and guide treatment.

Secondary myelofibrosis develops as a progression of other myeloproliferative disorders, most commonly polycythemia vera (PV) or essential thrombocythemia (ET). In these conditions, the bone marrow initially overproduces blood cells, but over time (usually after many years), fibrosis sets in, mimicking primary myelofibrosis. Patients with secondary myelofibrosis often have a history of PV or ET, and their treatment may involve managing both the original disorder and the resulting fibrosis. While the symptoms and complications are similar to PMF, the prognosis can vary depending on how well the underlying condition was controlled before fibrosis developed.

Understanding whether myelofibrosis is primary or secondary helps doctors determine the best treatment approach and predict long-term outcomes. Genetic testing and bone marrow biopsies play a crucial role in distinguishing between the two types.

Myelofibrosis is often called a "silent" disease in its early stages because many people experience mild or no symptoms initially. However, as the condition progresses, symptoms become more noticeable and can significantly impact daily life. The signs vary depending on how advanced the disease is, whether the spleen is enlarged, and how severely the bone marrow is affected. Below, we break down the most common symptoms in detail.

Fatigue and Weakness

One of the most common and debilitating symptoms of myelofibrosis is extreme fatigue and weakness, primarily caused by anemia (low red blood cell count). Since the scarred bone marrow can’t produce enough healthy red blood cells, the body doesn’t get sufficient oxygen, leading to exhaustion even after minimal activity. Patients often describe this fatigue as overwhelming, making it difficult to perform routine tasks.

Shortness of Breath

Due to anemia, many patients experience shortness of breath, especially during physical exertion. Even simple activities like climbing stairs or walking short distances can leave them gasping for air. In severe cases, breathlessness may occur even at rest, signaling a critical drop in oxygen levels.

Easy Bruising and Bleeding

Myelofibrosis disrupts platelet production, leading to thrombocytopenia (low platelet count). This can cause:

Unexplained bruising (even from minor bumps)

Frequent nosebleeds

Bleeding gums after brushing teeth

Heavy or prolonged bleeding from minor cuts

In rare cases, patients may develop petechiae (tiny red or purple spots on the skin), indicating bleeding under the skin.

Night Sweats and Fever

Many patients report drenching night sweats unrelated to room temperature or infections. Some also experience low-grade fevers without an obvious cause. These symptoms occur due to the body’s inflammatory response to abnormal blood cell production.

Bone and Joint Pain

As fibrosis worsens, the bone marrow expands, putting pressure on bones and causing aching pain, particularly in the legs, hips, and ribs. Some patients also develop gout-like joint pain due to high uric acid levels, a common complication of myelofibrosis.

Enlarged Spleen (Splenomegaly)

An enlarged spleen is one of the hallmark signs of myelofibrosis. As the spleen works overtime to filter abnormal blood cells, it can grow significantly, leading to:

Left-sided abdominal pain or fullness

Early satiety (feeling full quickly when eating)

Discomfort when bending or lying down

In extreme cases, the spleen can press on the stomach, causing unintentional weight loss due to reduced food intake.

Unintentional Weight Loss and Loss of Appetite

Many patients lose weight without trying, partly because the enlarged spleen compresses the stomach, reducing appetite. Additionally, the body’s increased metabolic rate due to chronic inflammation can contribute to weight loss.

Frequent Infections

Since myelofibrosis affects white blood cell production, patients become more susceptible to infections, including:

Recurrent colds or respiratory infections

Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

Slow-healing wounds

Severe cases may lead to life-threatening infections if white blood cell counts drop too low.

Less Common Symptoms

Itching (pruritus) – Some patients experience severe itching, especially after warm showers, due to histamine release.

Portal hypertension – If the spleen is extremely enlarged, it can increase blood pressure in the liver, leading to abdominal fluid buildup (ascites) or varices (enlarged veins in the esophagus).

When to See a Doctor

If you experience persistent fatigue, unexplained weight loss, severe abdominal pain, or frequent infections, consult a hematologist. Early diagnosis can help manage symptoms before complications arise.

Myelofibrosis is a complex disorder with no single definitive cause, but researchers have identified key factors that contribute to its development. Understanding these causes and risk factors can help in early detection and better management of the disease.

Most cases of myelofibrosis are linked to somatic mutations (acquired, not inherited) in certain genes that regulate blood cell production. The most common mutations found in myelofibrosis patients include:

JAK2 (Janus Kinase 2) Mutation – Present in about 50-60% of cases, this mutation causes bone marrow cells to grow and divide uncontrollably.

CALR (Calreticulin) Mutation – Found in 20-25% of patients, this mutation alters protein function in blood cell regulation.

MPL (Myeloproliferative Leukemia Virus Oncogene) Mutation – Seen in 5-10% of cases, this mutation affects platelet production and bone marrow function.

These mutations lead to abnormal signaling in the bone marrow, resulting in excessive scar tissue formation (fibrosis) and impaired blood cell production.

In some cases, myelofibrosis does not develop on its own but evolves from other myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), such as:

Polycythemia Vera (PV) – A condition where the bone marrow produces too many red blood cells. Over time, some PV patients develop myelofibrosis.

Essential Thrombocythemia (ET) – A disorder characterized by excessive platelet production, which can, in rare cases, progress to myelofibrosis.

This progression occurs due to ongoing genetic instability in the bone marrow, leading to worsening fibrosis over time.

While genetic mutations play the biggest role, certain environmental and lifestyle factors may increase the risk of developing myelofibrosis:

Exposure to Radiation or Toxic Chemicals – High levels of radiation (e.g., from cancer treatments) or prolonged exposure to industrial chemicals like benzene have been linked to bone marrow damage and an increased risk of myelofibrosis.

Age – The disease is most commonly diagnosed in adults over 50, with risk increasing with age.

Gender – Some studies suggest a slightly higher incidence in men than women, though the reason is unclear.

Family History – While not directly inherited, having a family history of MPNs may indicate a genetic predisposition.

Since most cases arise from random genetic mutations, myelofibrosis cannot be entirely prevented. However, reducing exposure to known carcinogens (like benzene and radiation) and maintaining regular medical check-ups—especially for those with other MPNs—can help in early detection and better disease management.

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a rare bone marrow disorder characterized by the replacement of healthy marrow with fibrous scar tissue, leading to impaired blood cell production. The disease progresses through different stages, which are primarily classified based on clinical, genetic, and pathological findings. While myelofibrosis does not have a formal staging system like solid tumors, physicians often assess disease progression using risk stratification models, symptom burden, and bone marrow changes. Below is a detailed breakdown of the key stages and classifications used in myelofibrosis.

In the early stages of myelofibrosis, patients may have mild or no symptoms. The bone marrow may show early signs of fibrosis, but blood cell production is still relatively functional. Common features of early-stage disease include mild anemia, slightly enlarged spleen (splenomegaly), and minimal constitutional symptoms such as fatigue or occasional night sweats. Patients in this stage typically have lower-risk genetic mutations (e.g., favorable karyotypes or absence of high-risk mutations like ASXL1 or TP53). The International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) categorizes these patients as low-risk, meaning they have a longer estimated survival (often 10–15 years) and may not require immediate aggressive treatment. Management often focuses on monitoring and symptom control rather than disease-modifying therapies.

As myelofibrosis progresses, patients enter an intermediate-risk phase, which is further divided into intermediate-1 and intermediate-2 categories based on prognostic scoring systems (DIPSS or MIPSS70+). In this stage, symptoms become more noticeable, including worsening anemia, significant splenomegaly, weight loss, night sweats, and bone pain. The bone marrow shows increased fibrosis, and blood tests may reveal abnormal white blood cell or platelet counts. Some patients may develop complications such as portal hypertension due to an enlarged spleen or require blood transfusions. Treatment strategies may include JAK inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib or fedratinib) to reduce spleen size and alleviate symptoms, along with supportive therapies like erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) for anemia.

High-risk myelofibrosis is characterized by severe bone marrow fibrosis, significant cytopenias (low blood counts), and debilitating symptoms. Patients in this stage often have high-risk genetic mutations, such as ASXL1, SRSF2, or TP53, which are associated with aggressive disease. Symptoms may include severe fatigue from anemia, frequent infections due to low white blood cells, bleeding risks from thrombocytopenia, and massive splenomegaly causing abdominal discomfort. The survival rate in this stage is significantly reduced (typically 2–4 years). Treatment options may include stem cell transplantation (the only potential cure), clinical trials, or palliative care for symptom management. Patients are also at higher risk of transforming to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which further worsens prognosis.

In some cases, myelofibrosis progresses to blast phase (also called leukemic transformation), where the bone marrow contains more than 20% blasts (immature blood cells), resembling acute myeloid leukemia (AML). This stage is aggressive, with rapid clinical deterioration, severe cytopenias, and poor response to chemotherapy. The prognosis is very poor, with a median survival of only a few months. Treatment options may include intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation, though outcomes remain unfavorable.

The diagnostic process for myelofibrosis begins with a thorough clinical evaluation and detailed medical history. Patients often present with symptoms such as fatigue, unexplained weight loss, night sweats, abdominal discomfort (due to an enlarged spleen), and easy bruising or bleeding. A history of prior blood disorders, exposure to radiation or chemicals, and family history of hematologic conditions may also be relevant. The physician assesses these factors to determine the likelihood of myelofibrosis and to rule out other potential causes of the symptoms.

2. Physical Examination

A physical examination is crucial in identifying signs of myelofibrosis. The most common finding is splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), which may cause abdominal fullness or pain. Hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) and lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes) may also be present. Additionally, the doctor may observe pallor (due to anemia), bruising (from low platelet counts), or signs of systemic inflammation. These findings help guide further diagnostic testing.

3. Blood Tests (Complete Blood Count and Peripheral Blood Smear)

Blood tests are essential in diagnosing myelofibrosis. A complete blood count (CBC) often reveals anemia, abnormal white blood cell counts (either high or low), and varying platelet levels (thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis). A peripheral blood smear may show teardrop-shaped red blood cells (dacrocytes), immature myeloid cells, and nucleated red blood cells, which are characteristic of myelofibrosis. Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels may also indicate increased cell turnover.

4. Bone Marrow Biopsy and Aspiration

A bone marrow biopsy is the gold standard for confirming myelofibrosis. The procedure involves extracting a small sample of bone marrow (usually from the hip bone) to examine under a microscope. In myelofibrosis, the bone marrow typically shows fibrosis (scarring) and abnormal megakaryocyte proliferation. An aspiration (removal of liquid marrow) may yield a "dry tap" due to the fibrotic changes. This test helps distinguish myelofibrosis from other myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) like polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia.

5. Genetic Testing (JAK2, CALR, and MPL Mutations)

Genetic testing plays a key role in diagnosing myelofibrosis. About 90% of patients have mutations in one of three genes: JAK2 V617F, CALR (calreticulin), or MPL. These mutations help confirm the diagnosis and differentiate myelofibrosis from other blood disorders. In rare cases, patients may be "triple-negative," lacking these mutations but still exhibiting clinical features of the disease. Additional molecular testing may be performed to assess prognosis and guide treatment decisions.

6. Imaging Studies (Ultrasound, CT, or MRI)

Imaging studies such as ultrasound, CT scans, or MRI may be used to evaluate spleen and liver size, especially if physical examination suggests significant enlargement. These tests help monitor disease progression and assess complications like portal hypertension (due to splenomegaly). In some cases, a PET scan may be recommended to rule out transformation into acute leukemia.

7. Differential Diagnosis and Exclusion of Other Conditions

Since myelofibrosis shares symptoms with other disorders, doctors must rule out conditions like chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), other MPNs, lymphoma, metastatic cancer, or autoimmune diseases. Additional tests, such as Philadelphia chromosome testing (BCR-ABL1) to exclude CML, may be performed. A comprehensive evaluation ensures an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan.

8. Prognostic Scoring Systems (IPSS, DIPSS, and MIPSS70)

Once diagnosed, prognostic scoring systems help determine disease severity and expected outcomes. The International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) and its revised versions (DIPSS, DIPSS-plus, and MIPSS70) consider factors like age, blood counts, genetic mutations, and symptoms to classify patients into low, intermediate, or high-risk categories. This stratification guides treatment decisions, including the potential need for stem cell transplantation.

The prognosis of myelofibrosis varies widely among patients, depending on factors such as age, genetic mutations, symptom severity, and overall health. While some individuals live for many years with manageable symptoms, others may experience rapid disease progression. Understanding the prognosis helps patients and doctors make informed decisions about treatment and lifestyle adjustments.

Several key factors influence the outlook for myelofibrosis patients:

1. Age and Overall Health: Younger patients (under 65) generally have a better prognosis because they are more likely to tolerate aggressive treatments like stem cell transplants. Older patients or those with additional health conditions (such as heart disease or diabetes) may face more complications.

2. Severity of Anemia: Low red blood cell counts (anemia) are a major predictor of disease progression. Patients with severe anemia often experience worse fatigue, higher transfusion dependency, and shorter survival rates. Hemoglobin levels below 10 g/dL are associated with a poorer prognosis.

3. Genetic Mutations: Certain genetic mutations impact survival rates:

JAK2 V617F mutation (present in ~50-60% of cases) – Linked to variable outcomes.

CALR mutation – Generally leads to a more favorable prognosis compared to JAK2.

High-risk mutations (ASXL1, SRSF2, U2AF1) – Associated with faster disease progression and higher risk of transforming into acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

4. Spleen Size and Symptoms: An enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) can cause pain, early satiety, and complications like portal hypertension. Patients with significant spleen enlargement often have more aggressive disease and may require medications like JAK inhibitors or even surgical removal.

5. Blast Cells in Blood or Bone Marrow: If the bone marrow or blood shows an increased number of immature cells (blast cells ≥ 10%), the risk of progressing to acute leukemia rises sharply. This is a critical factor in determining prognosis.

Doctors use specialized scoring models to predict disease progression and survival:

Used at diagnosis, it categorizes patients into low, intermediate-1, intermediate-2, and high-risk groups based on:

Age (> 65 years)

Hemoglobin level (< 10 g/dL)

White blood cell count (> 25 x 10⁹/L)

Presence of blast cells in blood (≥ 1%)

Constitutional symptoms (weight loss, night sweats, fever)

Estimated Survival Based on IPSS:

Low risk – Median survival ~11 years

Intermediate-1 – ~7-8 years

Intermediate-2 – ~4 years

High risk – ~2-3 years

These refined models adjust for disease progression over time and additional risk factors like:

Need for blood transfusions

Platelet count (< 100 x 10⁹/L)

Unfavorable karyotype (chromosomal abnormalities)

Myelofibrosis is a chronic condition that can remain stable for years or worsen suddenly. Possible progression pathways include:

1. Slow, Chronic Progression: Some patients experience gradual worsening of anemia and spleen enlargement but remain stable for a decade or longer with proper treatment.

2. Accelerated Phase: Increased fibrosis, worsening blood counts, and more severe symptoms may signal disease acceleration.

3. Transformation to Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML): About 10-20% of myelofibrosis cases evolve into AML, which is aggressive and difficult to treat. Survival after AML transformation is often measured in months rather than years.

Treating myelofibrosis requires a personalized approach, as the disease varies in severity from patient to patient. While there is no definitive cure (except for a stem cell transplant in eligible candidates), several treatment options and medications can help manage symptoms, slow disease progression, and improve quality of life. Below, we explore these treatments in detail.

The most effective medications for myelofibrosis are JAK inhibitors, which target the overactive JAK-STAT signaling pathway responsible for abnormal blood cell production and inflammation. The two main JAK inhibitors approved for myelofibrosis are:

Ruxolitinib (Jakafi®): This was the first JAK inhibitor approved for myelofibrosis and remains the cornerstone of treatment. It significantly reduces spleen size, alleviates constitutional symptoms (such as night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue), and improves overall survival in some patients. However, it can cause side effects like low blood counts (anemia, thrombocytopenia) and increased risk of infections.

Fedratinib (Inrebic®): Used for patients who cannot tolerate or do not respond to ruxolitinib, fedratinib also reduces spleen size and symptoms but carries a risk of serious neurological side effects, including Wernicke’s encephalopathy (a vitamin B1 deficiency-related brain disorder), requiring close monitoring.

Pacritinib (Vonjo®): Specifically approved for patients with severe thrombocytopenia (low platelet counts), pacritinib is an alternative for those who cannot take other JAK inhibitors due to blood count issues.

Many myelofibrosis patients develop severe anemia due to bone marrow failure. Treatments include:

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) like epoetin alfa or darbepoetin alfa to boost red blood cell production.

Danazol, a synthetic androgen, which can help improve hemoglobin levels in some patients.

Luspatercept (Reblozyl®), a newer drug that enhances red blood cell maturation, particularly useful in patients with associated ring sideroblast anemia.

Blood transfusions for severe, symptomatic anemia when other treatments fail.

Thalidomide and lenalidomide are sometimes used in combination with steroids to improve anemia and reduce spleen size, though their effectiveness is limited, and they can cause side effects like neuropathy and blood clots.

Several new drugs are being studied in clinical trials, including:

Momelotinib, a JAK inhibitor that also helps improve anemia by blocking hepcidin production (a hormone that restricts iron availability).

Navitoclax and pelabresib, which target different pathways involved in fibrosis and cancer cell survival.

Interferon-alpha, which may slow disease progression in early-stage myelofibrosis but is often poorly tolerated due to side effects.

1. Stem Cell Transplant (Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation - HCT)

The only potentially curative treatment for myelofibrosis is an allogeneic stem cell transplant, where a patient receives healthy stem cells from a matched donor. However, this is a high-risk procedure with significant complications, including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and infections, so it is typically reserved for younger, healthier patients with high-risk disease.

2. Splenectomy or Radiation for Enlarged Spleen

If the spleen becomes extremely enlarged (splenomegaly) and causes pain, early satiety, or severe cytopenias, surgical removal (splenectomy) may be considered, though it carries risks like bleeding and infection. Alternatively, spleen-directed radiation can provide temporary relief.

3. Supportive Care

Pain management for bone pain or spleen discomfort.

Antibiotics and antivirals to prevent infections, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Iron chelation therapy for patients who develop iron overload from frequent transfusions.

Since primary myelofibrosis is often caused by genetic mutations (such as JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutations), it cannot be entirely prevented. However, in cases where myelofibrosis develops secondary to other conditions like polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia, close monitoring and proper treatment of these precursor disorders may delay or reduce the risk of progression to myelofibrosis. For patients already diagnosed with myelofibrosis, the focus shifts to preventing complications rather than preventing the disease itself. Key strategies include:

Regular Monitoring and Early Intervention – Routine blood tests, bone marrow biopsies, and imaging (such as ultrasounds or MRIs to assess spleen size) help track disease progression. Early detection of worsening symptoms allows for timely adjustments in treatment.

Medications to Manage Symptoms – Drugs like JAK inhibitors (ruxolitinib, fedratinib) can reduce spleen size, alleviate constitutional symptoms (fatigue, night sweats, weight loss), and slow fibrosis progression. Hydroxyurea may also be used to control high blood cell counts.

Supportive Care for Anemia – Many myelofibrosis patients develop severe anemia due to bone marrow failure. Treatments may include erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), blood transfusions, or medications like danazol (a synthetic hormone that can boost red blood cell production).

Infection Prevention – Myelofibrosis weakens the immune system, making patients more susceptible to infections. Vaccinations (especially for influenza, pneumonia, and COVID-19), prophylactic antibiotics, and prompt treatment of infections are essential.

Bleeding Risk Management – Low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia) increase bleeding risk. Patients should avoid blood-thinning medications (like aspirin or NSAIDs) unless absolutely necessary and may require platelet transfusions in severe cases.

Lifestyle Modifications – A balanced diet, hydration, and moderate exercise (as tolerated) help maintain strength and reduce fatigue. Avoiding alcohol and smoking can also improve overall health.

Splenic Radiation or Surgery (Splenectomy) – If the spleen becomes excessively enlarged (splenomegaly), causing pain or complications, radiation or surgical removal may be considered, though these options carry risks (infection, bleeding, or liver enlargement post-splenectomy).

Stem Cell Transplant Consideration – The only potential cure for myelofibrosis is an allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT). However, this is high-risk and typically reserved for younger, healthier patients with a matched donor. Early referral to a transplant specialist is crucial for eligible candidates.

Myelofibrosis can lead to severe complications, particularly as the disease progresses. Understanding these risks helps patients and doctors take proactive measures.

Leukemia Transformation (Acute Myeloid Leukemia - AML)

About 10-20% of myelofibrosis patients eventually develop AML, an aggressive blood cancer. This occurs when abnormal bone marrow cells mutate further, leading to rapid, uncontrolled growth of immature white blood cells.

Symptoms of AML transformation include severe fatigue, frequent infections, easy bleeding, and bone pain. Treatment usually involves chemotherapy or stem cell transplant, but prognosis is often poor.

Severe Anemia and Bleeding Disorders

As fibrosis worsens, the bone marrow fails to produce enough red blood cells (anemia) and platelets (thrombocytopenia).

Anemia leads to extreme fatigue, shortness of breath, and heart strain. Some patients require regular blood transfusions.

Low platelets increase the risk of bruising, nosebleeds, and internal bleeding, which can be life-threatening if uncontrolled.

Portal Hypertension and Splenic Complications

An enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) is common in myelofibrosis and can cause pain, early satiety, and portal hypertension (increased blood pressure in the liver veins).

This may lead to varices (enlarged veins in the esophagus or stomach), which can rupture and cause severe bleeding.

In extreme cases, spleen removal (splenectomy) may be necessary, but this surgery carries risks like infection and blood clots.

Infections Due to Weakened Immunity

Low white blood cell counts (leukopenia) weaken the immune system, making patients prone to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

Preventative measures include vaccinations (flu, pneumonia, COVID-19), antibiotics, and avoiding crowded places during high-risk periods.

Bone and Joint Problems

Fibrosis can cause bone pain, osteoporosis, and fractures due to disrupted marrow function.

Some patients develop gout from high uric acid levels, a byproduct of rapid cell turnover.

Heart and Circulatory Issues

Chronic anemia forces the heart to work harder, increasing the risk of heart failure over time.

Abnormal blood cell production can also lead to blood clots (thrombosis), which may cause strokes or pulmonary embolisms.

Regular monitoring, medications (like JAK inhibitors), and supportive therapies (such as blood transfusions or growth factors) can help control complications. Stem cell transplantation remains the only potential cure but is only suitable for some patients due to its risks.

By recognizing these complications early, doctors can tailor treatments to improve survival and quality of life for myelofibrosis patients.

Myelofibrosis is a complex and chronic condition requiring careful management. While it poses significant health challenges, advances in JAK inhibitors and stem cell transplants offer hope for improved outcomes. If you or a loved one experience myelofibrosis symptoms and signs, early medical consultation is crucial for better disease control.

By staying informed and working closely with healthcare providers, patients can maintain a better quality of life despite this diagnosis.

Yes, myelofibrosis is considered a type of blood cancer because it involves the abnormal growth and malfunction of bone marrow stem cells. The excessive scarring (fibrosis) and uncontrolled production of abnormal blood cells classify it as a chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm, which falls under the broader category of hematologic malignancies. While it progresses more slowly than acute leukemias, it can transform into acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in some cases.

The survival rate for myelofibrosis varies depending on factors like age, overall health, genetic mutations, and disease progression. On average:

Low-risk patients may live 10–15 years or more with proper management.

Intermediate-risk patients have a median survival of about 5–7 years.

High-risk patients may survive 2–3 years without aggressive treatment.

Prognosis is often assessed using scoring systems like the Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System (DIPSS).

The end stage (also called blast phase) occurs when myelofibrosis transforms into acute myeloid leukemia (AML), marked by a rapid increase in immature blast cells. Symptoms worsen significantly, including:

Severe anemia (requiring frequent transfusions)

Uncontrolled bleeding or infections

Extreme fatigue and weight loss

Massive spleen enlargement causing pain and discomfort

At this stage, treatment options are limited, and survival is typically short (a few months).

Yes, myelofibrosis can be painful due to:

Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly): Causes abdominal pain, early satiety, and pressure.

Bone pain: Resulting from bone marrow expansion and fibrosis.

Gout or joint pain: Due to high uric acid levels from cell turnover.

Pain management may involve medications, splenectomy (spleen removal), or targeted therapies.

While not directly inherited, myelofibrosis is associated with acquired genetic mutations, most commonly:

JAK2 V617F (present in ~50–60% of cases)

CALR (~20–30%)

MPL (~5–10%)

These mutations lead to abnormal blood cell production. Rarely, familial cases exist, but most occur sporadically.

Myelofibrosis is typically classified by risk (low, intermediate, high) rather than stages. However, Stage 3 (if referring to advanced disease) involves:

High-risk features (severe anemia, high blast count, worsening fibrosis)

Increased dependency on blood transfusions

Higher likelihood of progression to AML

Treatment at this stage may focus on palliative care or bone marrow transplant (if eligible).

A bone marrow transplant (BMT), or allogeneic stem cell transplant, is the only potential cure for myelofibrosis. However:

It is high-risk, with significant complications (graft-versus-host disease, infections).

Best suited for younger, healthier patients with a matched donor.

Success rates vary, with 5-year survival around 40–60% in eligible patients.

Myelofibrosis is managed by specialists such as:

Hematologists/Oncologists (blood cancer experts)

Transplant specialists (for BMT evaluation)

Supportive care teams (for symptom management)

Treatment may include JAK inhibitors (ruxolitinib, fedratinib), chemotherapy, blood transfusions, or clinical trials.

Survival after a bone marrow transplant depends on:

Age and overall health (better outcomes in younger patients).

Donor match (fully matched donors improve success).

Disease stage (early transplants have higher success).

While risky, long-term survival is possible, with some patients achieving complete remission.

Myelofibrosis is generally not reversible with standard treatments. However:

Bone marrow transplant can potentially reverse fibrosis in successful cases.

JAK inhibitors (like ruxolitinib) reduce symptoms but do not cure the disease.

Experimental therapies (e.g., interferon, BET inhibitors) are being studied for fibrosis reversal.

You Might Also Like