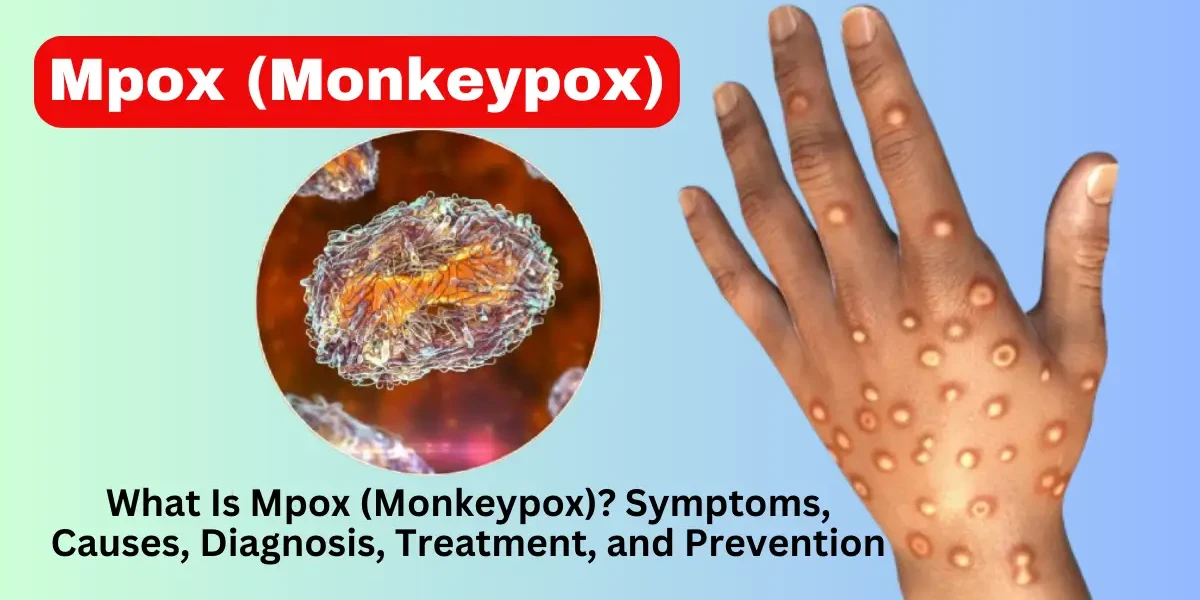

Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, is a rare but potentially serious viral disease that has gained global attention due to recent outbreaks. While it was once primarily confined to Central and West Africa, cases have now been reported in various parts of the world, raising public health concerns.

Mpox is caused by the monkeypox virus, a member of the Orthopoxvirus family, which also includes the now-eradicated smallpox virus. The disease was first discovered in 1958 in laboratory monkeys (hence the name), but its primary hosts are actually rodents and other small mammals.

Human infections were rare until recent years, with most cases occurring in regions where the virus is endemic, such as parts of Africa. However, since 2022, outbreaks have been reported in non-endemic countries, leading to increased awareness and research.

The virus spreads through:

Close physical contact (skin-to-skin, respiratory droplets)

Contaminated objects (bedding, clothing)

Animal bites or scratches (from infected animals)

Unlike COVID-19, mpox does not spread as easily through the air, but prolonged close contact increases transmission risk.

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus, which belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus—the same family as smallpox and cowpox. Scientists have identified two major genetic clades (types) of the virus, each with distinct characteristics in terms of transmission, severity, and geographic distribution. Understanding these types is crucial for public health responses, vaccine development, and treatment strategies.

Clade I is the more severe form of monkeypox, historically linked to outbreaks in Central Africa, particularly the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). This strain has a higher fatality rate (up to 10%), making it a significant public health concern in regions where it is endemic.

Key Features of Clade I:

More aggressive disease progression – Patients often experience severe systemic symptoms, including high fever, extensive rash, and complications like pneumonia.

Higher human-to-human transmission – Some studies suggest that Clade I spreads more efficiently between people compared to Clade II.

Endemic in rainforest regions – The virus circulates among rodents and other small mammals, occasionally spilling over into humans through hunting or bushmeat handling.

Due to its severity, outbreaks of Clade I require rapid containment measures, including isolation of cases, contact tracing, and vaccination of high-risk groups.

Clade II is the less severe but more widespread type of monkeypox. It was first identified in West Africa, particularly in Nigeria, where sporadic outbreaks have occurred since the 1970s. The 2022 global outbreak was primarily driven by a subtype of Clade II, known as Clade IIb, which showed increased human-to-human transmission.

Key Features of Clade II:

Lower fatality rate (1-3%) – Most cases are mild, with recovery occurring within a few weeks.

Milder symptoms – While patients still develop a rash and flu-like illness, severe complications are less common.

Adapted better to human transmission – The 2022 outbreak suggested that Clade IIb had mutations that made it more contagious outside traditional animal reservoirs.

Clade II is the dominant strain in recent international cases, emphasizing the need for global surveillance and vaccination campaigns in non-endemic countries.

Treatment and vaccine effectiveness – Some evidence suggests that antiviral drugs and vaccines may work differently against each clade.

Public health strategies – Outbreak responses must consider whether they are dealing with the more lethal Clade I or the more transmissible Clade II.

Research and surveillance – Tracking genetic changes in the virus helps predict future outbreaks and adjust medical interventions.

Monkeypox symptoms typically develop in two main phases: an early systemic (whole-body) phase and a later rash phase. The illness usually begins 5 to 21 days after exposure, with most people showing symptoms within 1 to 2 weeks.

Before the rash appears, most people experience flu-like symptoms, which can make early diagnosis tricky since they resemble other viral infections. These include:

Fever – Often the first sign, with temperatures rising above 38.3°C (101°F).

Chills and Sweating – The body’s response to infection, similar to the flu.

Swollen Lymph Nodes – A key feature that distinguishes monkeypox from smallpox. Lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin may become tender and enlarged.

Severe Fatigue – Many patients report extreme tiredness, making daily activities difficult.

Muscle Aches and Back Pain – Deep soreness, similar to what some experience with severe influenza.

Headache – Often intense and persistent.

These symptoms last for about 1 to 3 days before the rash emerges, though some people develop the rash at the same time as the fever.

The monkeypox rash is its most distinctive feature, progressing through several stages over 2 to 4 weeks. Unlike chickenpox—where lesions appear in waves—monkeypox sores tend to develop at the same pace in a given area.

Enanthem (Early Mouth/Throat Lesions, Sometimes)

Some patients first develop sores inside the mouth, throat, or genitals before skin lesions appear.

These can be painful, making eating or drinking difficult.

Macules (Flat, Red Spots)

The rash starts as small, flat, red spots, usually on the face, hands, feet, or mouth before spreading.

In recent outbreaks, some patients have had initial lesions in the genital or anal area, especially if transmission occurred through intimate contact.

Papules (Raised Bumps)

Within 1 to 2 days, the spots become raised, firm, and often painful or itchy.

Vesicles (Fluid-Filled Blisters)

By day 4 to 5, the bumps fill with clear fluid, resembling blisters.

Pustules (White/Yellow Pus-Filled Bumps)

The blisters turn into pus-filled pustules, which may look like severe acne or boils.

This stage is often the most painful, with swelling and tenderness.

Scabs (Drying and Crusting Over)

After about 7 to 14 days, the pustules dry up, forming scabs.

Once all scabs have fallen off (usually by week 3 or 4), the person is no longer contagious.

Face (95% of cases) – Often the first area affected.

Palms and Soles (75%) – A distinguishing feature from chickenpox.

Mouth, Genitals, or Eyes (30%) – Can be particularly painful if lesions form in these areas.

Torso and Limbs – Spreads outward from the initial site.

Some patients in the 2022-2023 outbreaks had only a few sores, sometimes just one or two, making diagnosis harder.

Lesions in the genital or anal region were more common in cases linked to sexual contact.

A small number of people had no early flu-like symptoms, developing the rash first.

Seek medical attention if you:

✔ Develop an unexplained rash after close contact with someone who has monkeypox.

✔ Have flu-like symptoms followed by painful blisters.

✔ Are at high risk (immunocompromised, pregnant, or caring for someone with monkeypox).

Early diagnosis helps with treatment and prevents further spread.

The monkeypox virus (MPXV) is transmitted to humans through close contact with infected animals or people, as well as contaminated materials. Understanding how it spreads and who is most vulnerable helps in prevention and early intervention.

Animal-to-Human Transmission

The virus naturally circulates in wild animals, particularly rodents (like squirrels and rats) and non-human primates. Humans can contract monkeypox through:

Bites or scratches from infected animals

Handling bushmeat (wild animal meat)

Direct contact with an infected animal’s blood, fluids, or lesions

In Africa, cases often arise in rural areas where people hunt or live near wildlife.

Human-to-Human Transmission

Once a person is infected, they can spread the virus to others through:

Skin-to-skin contact with infectious rashes, scabs, or bodily fluids

Respiratory droplets (prolonged face-to-face contact, such as kissing or caring for a sick person)

Contaminated objects (bedding, towels, clothing, or surfaces touched by an infected person)

Unlike COVID-19, monkeypox does not spread easily through casual contact or brief interactions. Most transmissions occur in households, healthcare settings, or intimate relationships.

Sexual Contact (Recent Observations)

The 2022 global outbreak showed that sexual contact played a significant role in transmission, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM). The virus spreads through skin-to-skin contact during sex, not necessarily through semen or vaginal fluids. However, any close physical contact (with rashes or lesions) can transmit the infection.

Certain groups are more likely to contract monkeypox or experience severe illness:

People with Multiple Sexual Partners

Recent outbreaks have shown higher infection rates in sexually active individuals, especially those with multiple partners.

MSM communities were disproportionately affected in 2022, but the virus can infect anyone regardless of sexual orientation.

Household Contacts & Caregivers

Family members, roommates, or healthcare workers caring for infected patients are at risk if proper precautions (gloves, masks, disinfection) are not taken.

Immunocompromised Individuals

Those with HIV/AIDS, cancer, or autoimmune diseases may experience more severe symptoms due to weaker immune defenses.

Children & Pregnant Women

Children (especially under 8) may develop more severe rashes or complications like pneumonia.

Pregnant women risk passing the virus to the fetus, leading to pregnancy complications.

Travelers to Endemic Regions

Visiting areas in Central or West Africa where monkeypox is common increases exposure risk.

Unlike COVID-19, asymptomatic spread is rare. Most transmissions occur after symptoms appear, especially once rashes develop.

However, early flu-like symptoms (before rashes) can still spread the virus through respiratory droplets in close contact.

Monkeypox is a viral disease that progresses through different stages. The illness typically lasts between 2 to 4 weeks, and the stages include incubation, prodrome (early symptoms), rash development, and recovery.

1. Incubation Stage: The incubation period is the time between exposure to the virus and the appearance of symptoms. This stage usually lasts 5 to 13 days, but it can range from 4 to 21 days. During this phase, the person does not show any symptoms, but the virus is multiplying inside the body.

2. Prodrome Stage (Early Symptoms): After the incubation period, early flu-like symptoms appear. These may include fever, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, and swollen lymph nodes. Swollen lymph nodes are a key difference between monkeypox and other similar diseases like chickenpox. This stage lasts 1 to 4 days before the rash develops.

3. Rash Development Stage: A rash usually begins 1 to 3 days after the fever starts. It first appears on the face and then spreads to other body parts, including the hands, feet, and genital area. The rash goes through different phases:

Macules (flat, discolored spots)

Papules (raised bumps)

Vesicles (fluid-filled blisters)

Pustules (pus-filled sores)

Scabs (drying and healing)

The rash can be painful or itchy and usually lasts 2 to 4 weeks before scabbing over.

4. Recovery Stage: Once the scabs fall off, the person is no longer contagious. The skin heals, but it may leave light scars or dark spots where the rash was. Most people recover fully, but those with weak immune systems may have more severe symptoms.

Most people recover within 2-4 weeks, but severe cases may require hospitalization.

Diagnosing mpox (monkeypox) requires a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing because its early symptoms can resemble other infections like chickenpox, herpes, or even allergic reactions. Doctors follow a structured approach to confirm the disease, especially in areas where mpox is not common.

The first step in diagnosing mpox is a detailed medical history and physical exam. Doctors look for:

Fever, swollen lymph nodes, and fatigue (early symptoms).

The characteristic rash, which progresses from flat red spots to fluid-filled blisters and then scabs.

Recent exposure to someone with mpox or travel to regions with known outbreaks.

Since mpox shares symptoms with other diseases (such as varicella-zoster virus or hand, foot, and mouth disease), lab tests are essential for confirmation.

The most accurate way to diagnose mpox is through PCR testing, which detects the virus’s genetic material. Here’s how it works:

A healthcare provider swabs a lesion (blister, scab, or fluid) to collect a sample.

The sample is sent to a specialized lab that can identify the monkeypox virus.

Results are usually available within 24 to 72 hours, depending on lab capacity.

PCR testing is highly reliable if done correctly, but false negatives can occur if the sample is taken too early (before lesions form) or too late (after scabs have dried).

While PCR is the primary diagnostic tool, blood tests may be used in certain situations:

Antibody tests can detect if a person was recently infected, but they are not always reliable because smallpox vaccination (which some older adults received) can cause cross-reactive antibodies.

Viral culture (growing the virus in a lab) is possible but rarely used due to the risk of lab exposure.

In unusual cases where the rash looks different or complications arise, a skin biopsy may be performed. A small piece of affected skin is examined under a microscope to confirm mpox.

Monkeypox can be confused with several other conditions, making differential diagnosis essential:

Chickenpox (Varicella-zoster virus): Lesions appear in successive crops, affecting different body parts simultaneously, whereas monkeypox lesions typically develop synchronously in a given area.

Smallpox: Now eradicated, it lacked lymphadenopathy but had a similar rash progression.

Herpes Simplex or Syphilis: These can cause genital or oral ulcers resembling monkeypox but require different treatments.

Molluscum Contagiosum: Presents with pearly, umbilicated papules but no systemic symptoms.

Most cases are mild, with full recovery in weeks. However:

Severe cases can lead to secondary infections (bacterial skin infections).

Complications like pneumonia, sepsis, or eye infections may occur.

Immunocompromised individuals, children, and pregnant women face higher risks.

The fatality rate is low (1-3%) for Clade II but higher for Clade I.

Monkeypox, caused by the Monkeypox virus (MPXV), is a viral disease that can cause a painful rash, fever, and swollen lymph nodes. While most cases are mild and resolve on their own, some patients—particularly those with weakened immune systems—may require medical treatment. Currently, there is no cure for monkeypox, but several antiviral medications and supportive care strategies can help manage symptoms, reduce complications, and speed up recovery. This article will provide an in-depth discussion of monkeypox treatment options, including FDA-approved medications, off-label therapies, and supportive care measures.

Since most monkeypox cases are self-limiting (resolving without treatment), supportive care is the primary approach. This involves managing symptoms and preventing secondary infections. Key aspects include:

Fever and Pain Management: Over-the-counter (OTC) medications like acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) can help reduce fever and relieve pain from lesions. Aspirin should be avoided in children due to the risk of Reye’s syndrome.

Hydration and Rest: Patients should drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration, especially if they have mouth sores that make eating or drinking difficult.

Skin Care: Keeping lesions clean and dry helps prevent bacterial superinfections. Patients should avoid scratching to minimize scarring and secondary infections. Warm baths with colloidal oatmeal or Epsom salts may soothe itching.

Oral Care: If mouth ulcers are present, rinsing with saltwater or prescription mouthwashes (e.g., lidocaine-based solutions) can ease discomfort.

Isolation: To prevent transmission, patients should isolate until all scabs have fallen off and new skin has formed (typically 2–4 weeks).

While most patients recover without antivirals, certain high-risk groups may benefit from prescription medications. These include:

Immunocompromised individuals (e.g., HIV patients, chemotherapy recipients)

Children under 8 years old (higher risk of severe disease)

Pregnant or breastfeeding women

Patients with severe disease (e.g., widespread rash, sepsis, or organ involvement)

1. Tecovirimat (TPOXX, ST-246)

Mechanism: Inhibits viral replication by blocking the VP37 protein, preventing the virus from spreading between cells.

Administration: Available in oral (capsules) and intravenous (IV) forms.

Dosage:

Adults & Children (≥13 kg): 600 mg orally twice daily for 14 days.

Children (<13 kg): Weight-based dosing (consult CDC guidelines).

Effectiveness: Studies show it reduces symptom duration and viral shedding.

Side Effects: Generally well-tolerated; possible headache, nausea, or mild abdominal pain.

Access: Requires special permission from the CDC due to limited supply (available under an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug protocol).

Mechanism: A lipid-conjugated version of cidofovir, it inhibits viral DNA polymerase, stopping viral replication.

Administration: Oral tablets.

Dosage:

Adults & Children (≥10 kg): Single weekly dose for 1–2 weeks.

Effectiveness: Effective against orthopoxviruses but may cause liver toxicity.

Side Effects: Elevated liver enzymes, diarrhea, nausea.

Use Case: Reserved for severe cases when tecovirimat is unavailable.

Mechanism: Similar to brincidofovir but with higher toxicity.

Administration: IV infusion.

Drawbacks: Risk of kidney damage; requires probenecid and IV hydration to mitigate toxicity.

Current Role: Rarely used due to safer alternatives.

1. Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous (VIGIV)

Mechanism: Contains antibodies from vaccinated donors, providing passive immunity.

Use Case: May help severe cases or immunocompromised patients, but evidence is limited.

Administration: IV infusion.

2. Trifluridine Ophthalmic Solution (for Eye Infections)

Use: If monkeypox lesions affect the eyes, this antiviral eye drop can prevent corneal damage.

While not a treatment, vaccination after exposure can prevent or lessen disease severity. Two vaccines are available:

A. JYNNEOS (Imvamune, Imvanex)

Type: Non-replicating live virus vaccine (safer for immunocompromised individuals).

Dosage: Two doses, 28 days apart.

Effectiveness: Up to 85% effective if given within 4 days of exposure (may still reduce severity if given up to 14 days post-exposure).

B. ACAM2000

Type: Live vaccinia virus (replicating), derived from smallpox vaccine.

Risks: Not recommended for immunocompromised or pregnant patients due to potential side effects (myocarditis, eczema vaccinatum).

Preventing monkeypox primarily involves reducing exposure to the virus, practicing good hygiene, and, in certain cases, vaccination. The monkeypox virus spreads through close contact with infected individuals or animals, contaminated materials, or respiratory droplets in prolonged face-to-face interactions. To minimize the risk of infection, the following preventive measures should be taken:

Avoid Close Contact with Infected Individuals or Animals

Monkeypox can be transmitted through direct skin-to-skin contact with lesions, bodily fluids, or respiratory secretions of an infected person. Additionally, handling infected animals (particularly rodents and primates) or consuming undercooked meat from infected animals can increase transmission risk. Isolating infected individuals and avoiding contact with wild or sick animals are essential preventive steps.

Practice Good Hand Hygiene

Regular handwashing with soap and water or using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer helps eliminate the virus from the skin, reducing the risk of transmission, especially after touching contaminated surfaces or caring for an infected person.

Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Healthcare workers and caregivers should wear gloves, masks, and gowns when handling patients with monkeypox or contaminated materials. Proper disposal of PPE and disinfection of surfaces are critical in preventing nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections.

Safe Handling of Contaminated Materials

Clothing, bedding, and medical equipment used by infected individuals should be handled with care, washed with hot water and detergent, and disinfected appropriately to prevent viral spread.

Vaccination

The smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) and the newer JYNNEOS (Imvamune/Imvanex) vaccine have shown effectiveness against monkeypox. Vaccination is recommended for high-risk groups, including healthcare workers, laboratory personnel handling orthopoxviruses, and individuals who have had close contact with confirmed cases. Post-exposure vaccination (within 4 days of exposure) may also prevent or reduce disease severity.

Public Health Measures

Contact tracing, quarantine of exposed individuals, and public awareness campaigns are vital in controlling outbreaks. Travelers to endemic regions (Central and West Africa) should take extra precautions to avoid exposure.

While most monkeypox cases are mild and self-limiting, certain populations—such as immunocompromised individuals, children, pregnant women, and those with underlying skin conditions—are at higher risk of severe disease and complications. Potential complications include:

Secondary Bacterial Infections

The skin lesions caused by monkeypox can become superinfected with bacteria, leading to cellulitis, abscesses, or sepsis if untreated. Proper wound care and antibiotics may be necessary in such cases.

Scarring and Skin Disfigurement

Severe monkeypox lesions, especially if scratched or improperly managed, can result in permanent scarring or hyperpigmentation.

Ocular Complications

If the virus spreads to the eyes (via touching lesions and then the eyes), it can cause conjunctivitis, keratitis, corneal scarring, and even blindness in extreme cases.

Respiratory Distress

In rare instances, extensive respiratory involvement can lead to pneumonia, bronchopneumonia, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), particularly in severe cases or immunocompromised patients.

Encephalitis and Neurological Complications

Although rare, the monkeypox virus can invade the central nervous system, leading to encephalitis (brain inflammation), seizures, or long-term neurological deficits.

Dehydration and Malnutrition

Painful oral or throat lesions can make eating and drinking difficult, leading to dehydration and malnutrition, especially in children. Intravenous fluids or nutritional support may be required in severe cases.

Systemic Infection and Multi-organ Failure

In very severe cases (particularly in immunocompromised individuals), the virus can disseminate widely, causing multi-organ failure, septic shock, and death. The case fatality rate varies by strain (1-10%), with the Congo Basin clade being more virulent than the West African clade.

Psychological Impact

The visible lesions, social stigma, and isolation required during infection can lead to anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in some patients.

Mpox (monkeypox) is a treatable but contagious disease that requires awareness and preventive measures. While most cases are mild, high-risk groups should take extra precautions.

By understanding monkeypox symptoms, causes, and prevention, we can reduce transmission and protect vulnerable populations. If you suspect exposure, seek medical advice promptly—early intervention is key.